USMLE/COMLEX 3 - GI Bleeding

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for USMLE Step 3 & COMLEX-USA Level 3 from the GI Bleeding tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

- --

VITAL FOR USMLE/COMLEX 3

Clinical Assessment of GI Bleeding

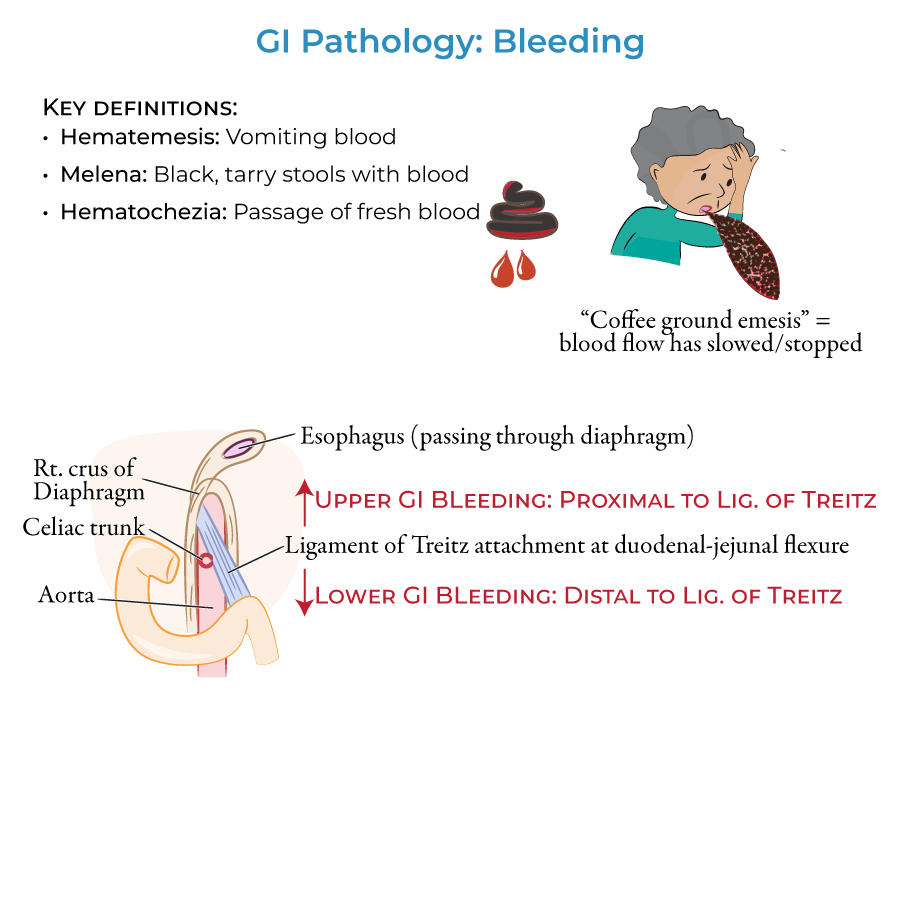

1. Hematemesis (vomiting blood) indicates an upper GI source of bleeding.

2. "Coffee ground" appearance of vomit indicates that blood flow has slowed or stopped, helping with timing assessment.

3. Melena (black, tarry stools) can indicate upper GI or proximal lower GI bleeding.

4. Hematochezia (bright red blood per rectum) typically indicates lower GI source but can occur with massive upper GI bleeding.

5. Upper GI bleeding produces hematemesis and/or melena; lower GI bleeding produces melena and/or hematochezia.

Anatomical Considerations for Management

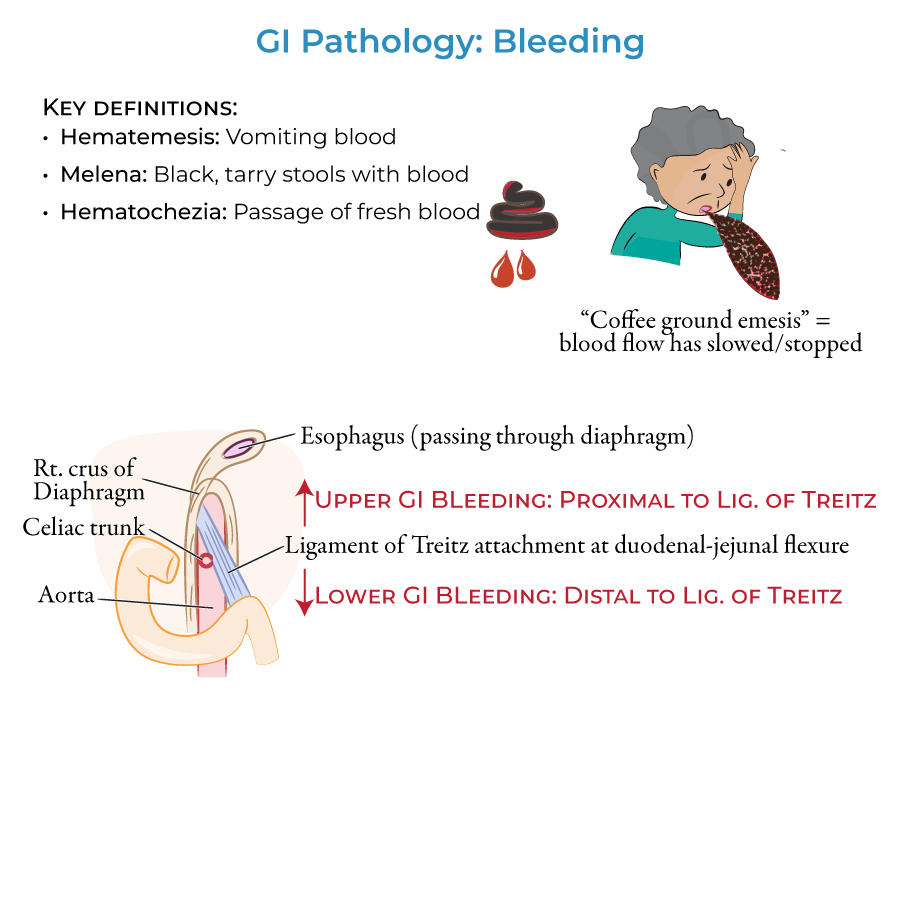

1. The Upper Gastrointestinal tract lies proximal to the duodenal attachment of the ligament of Treitz (suspensory ligament of the duodenum) and the Lower Gastrointestinal tract lies distal to it.

Life-Threatening Upper GI Bleeding

1. Duodenal and gastric ulcers & erosion are most common cause of upper GI bleeding, typically resulting from H. pylori infection, drugs, stress, or autoimmune disorders.

2. Varices in the esophagus and proximal stomach can rupture and cause potentially life-threatening hemorrhages, associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

3. Mallory-Weiss tears occur in the distal esophagus from fits of violent vomiting or coughing.

4. Esophagitis leads to erosion of the esophageal lining and bleeding, associated with severe acid reflux and alcohol consumption.

Critical Lower GI Bleeding Management

1. Diverticular hemorrhage is a top cause of lower GI bleeding characterized by brisk hematochezia with possibility of massive bleeding.

2. Inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis, causes bloody diarrhea when active.

3. Infectious colitis, particularly bacterial, can produce fever, tenesmus, abdominal pain, and purulent, loose bloody stools.

4. C. difficile infection following antibiotic use requires specific management protocols.

5. Acute and chronic intestinal ischemia causes lower GI bleeding along with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Differential Diagnosis Pearls

1. Esophagitis erosion is most often associated with severe acid reflux and alcohol consumption.

2. Mallory-Weiss tears are rare compared to other causes of upper GI bleeding.

3. Varices are most often associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension and require specialized management.

4. Viral colitis is associated with watery diarrhea and is more common in infants and children.

5. Amoebic colitis is associated with diarrhea and mucoid discharge, requiring antiparasitic treatment.

Characteristic Findings

1. Ulcerative colitis is characterized by mucosal and submucosal inflammation with sunken ulcers that create a friable or crumbly appearance.

2. Diverticula are not necessarily inflamed when bleeding occurs in diverticular hemorrhage.

3. Anal fissures produce bright, fresh blood and cause pain during and after bowel movements.

4. Neoplasms can occur anywhere along the GI tract and are often the presenting sign.

5. Hemorrhoids are swollen veins in rectum and perianal region that can rupture and produce hematochezia.

Vascular Causes

1. Arteriovenous malformations are atypical arrangements of blood vessels that divert blood from their proper targets; the tangled vessels can rupture and cause bleeding. These are rare.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Acute Management Protocols

1. Initial resuscitation with two large-bore IVs, crystalloid fluids, and blood products as needed based on hemodynamic status.

2. Risk stratification using validated scoring systems (Glasgow-Blatchford, AIMS65) to determine level of care and urgency of intervention.

3. Pre-endoscopic management with proton pump inhibitors for suspected upper GI bleeding.

4. Octreotide and prophylactic antibiotics for suspected variceal bleeding.

5. Reversal of anticoagulation when appropriate, balanced against thrombotic risk.

Endoscopic and Interventional Management

1. Timing of endoscopy based on risk stratification (within 24 hours for most upper GI bleeding, after bowel prep for lower GI bleeding).

2. Endoscopic interventions include injection therapy, thermal coagulation, mechanical therapy (clips, banding).

3. Interventional radiology with embolization for bleeding not controlled by endoscopic measures.

4. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for refractory variceal bleeding.

5. Surgical options including oversewing of ulcers, segmental resection for uncontrolled diverticular bleeding.

Post-Acute Care and Prevention

1. H. pylori testing and eradication for peptic ulcer disease.

2. Assessment of need for continued NSAID use and gastroprotection strategies.

3. Beta-blockers and endoscopic surveillance for patients with esophageal varices.

4. Long-term anticoagulation management in patients with history of GI bleeding.

5. Colonoscopy for cancer screening after resolution of lower GI bleeding in appropriate age groups.

Special Considerations

1. Management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with recent coronary stents who develop GI bleeding.

2. Angiodysplasia association with aortic stenosis, von Willebrand disease, and chronic kidney disease.

3. Recurrent obscure GI bleeding workup, including capsule endoscopy and deep enteroscopy.

4. Dieulafoy's lesion as cause of massive, unexplained bleeding requiring specialized endoscopic detection techniques.

5. Rectal varices versus hemorrhoids in patients with portal hypertension.