USMLE/COMLEX 3 - Gastritis & Peptic Ulcer Disease

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for USMLE Step 3 & COMLEX-USA Level 3 from the Gastritis & Peptic Ulcer Disease tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for USMLE & COMLEX 3.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for USMLE & COMLEX 3.

- --

VITAL FOR USMLE/COMLEX 3

Management Principles

1. Treatment of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease involves proton pump inhibitors, NSAID discontinuation, and, when present, H. pylori eradication with antibiotics.

2. In the case of H. pylori infection, perform follow-up tests to confirm eradication and avoid relapse.

3. Non-ulcer dyspepsia is treated with proton pump inhibitors after ruling out cancer in those over 55 years old.

4. Hemorrhage complications can be treated with endoscopic hemostasis therapies and proton pump inhibitors.

5. For gastric outlet obstruction, try treatment of the underlying peptic ulcer disease before attempting surgical solutions.

Diagnostic Decision Making

1. For patients younger than 60 years without alarming symptoms, focus on diagnosis of active H. pylori infection with non-invasive testing and response to a proton pump inhibitor.

2. Urea breath test and stool antigen tests are preferred non-invasive methods for detecting active H. pylori infection.

3. H. pylori antibody serologies do not distinguish between active and inactive disease.

4. For patients older than 60 years or with any alarming symptoms (weight loss, anemia, bloody stools, dysphagia), upper endoscopy should be performed.

5. Diagnosis relies on upper endoscopy to visualize potential lesions and biopsies to look for signs of inflammation, H. pylori infection, and malignancy.

Emergency Management

1. Perforation is an emergency that can cause peritonitis and has a high mortality rate (up to 30%).

2. Patients with perforation present with sudden abdominal pain, tachycardia, and abdominal rigidity.

3. Imaging of perforation will show free abdominal air under the diaphragm (pneumoperitoneum).

4. Hemorrhagic bleeding can be deadly, requiring prompt treatment with proton pump inhibitors.

5. Stress ulcers require preventive care in high-risk patients with systemic burns (Curling ulcers) or brain injury (Cushing ulcers).

- --

HIGH YIELD

Differential Diagnosis

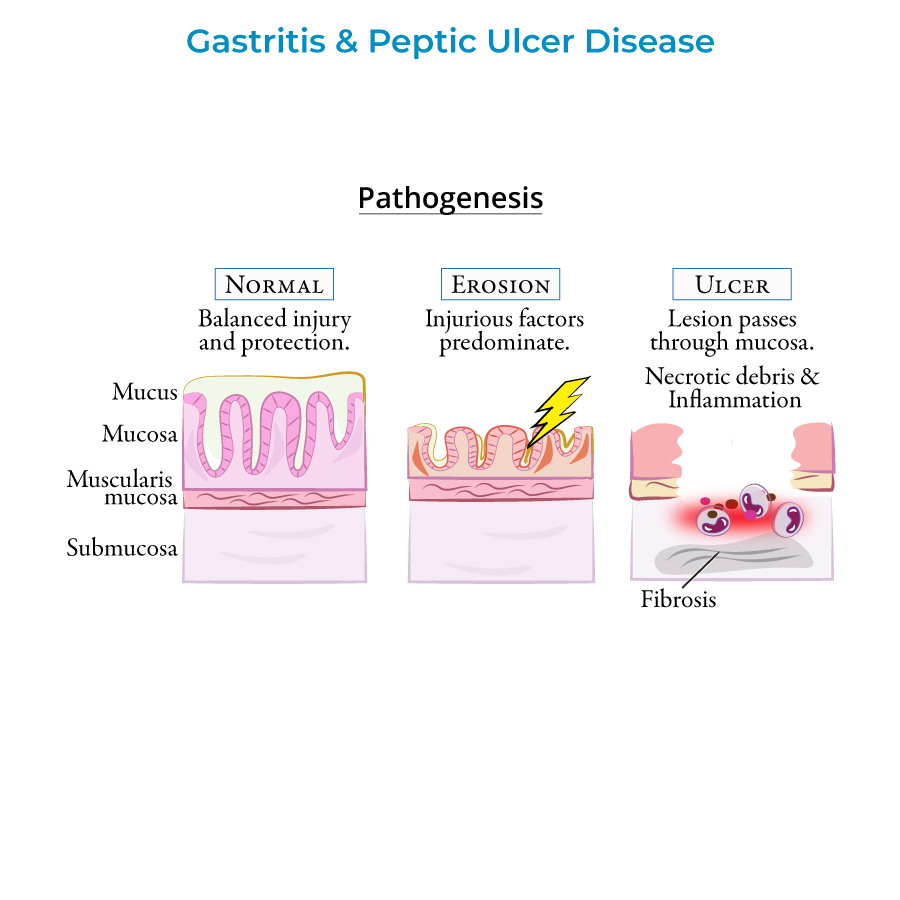

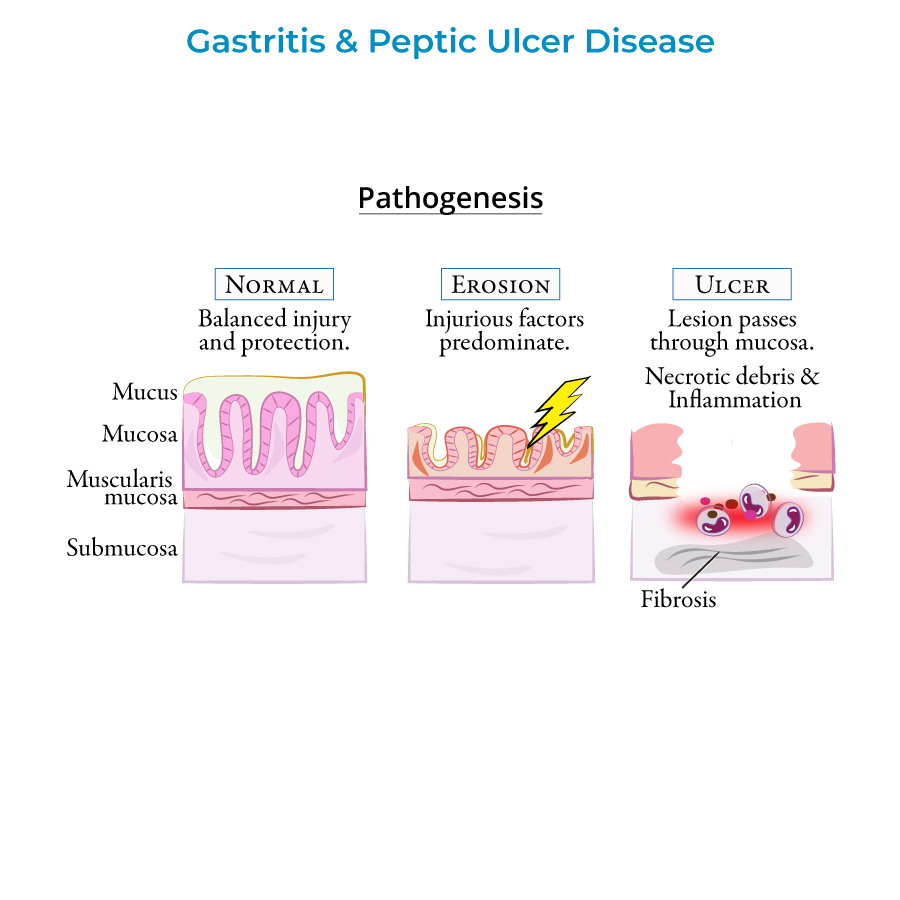

1. Gastritis is characterized by mucosal inflammation, while gastropathy refers to gastric mucosal disorders without inflammation.

2. Gastric ulcers (reduced mucosal protection) have higher malignancy risk (5-10%) than duodenal ulcers (typically benign).

3. Acute gastritis presents with interstitial hemorrhaging, capillary dilation, and necrotic debris (fibrin and neutrophils).

4. Chronic gastritis can lead to atrophy, characterized by loss of gastric glands and folds with increased risk of malignancy.

5. "Penetration" occurs when a peptic ulcer erodes into another organ instead of opening into the peritoneum.

Management Considerations

1. Early detection and treatment of gastric ulcers is crucial because of their higher risk of malignancy.

2. Peptic ulcers caused by H. pylori are declining due to improved sanitation, while NSAID-related cases are increasing.

3. Gastric outlet obstruction in acute cases is due to inflammation and edema; in chronic cases, it's due to fibrosis and scarring.

4. Autoimmune gastritis can be concomitant with H. pylori infection, requiring checking for and treating H. pylori even when autoimmune etiology is indicated.

5. Perforation has a high mortality rate (up to 30%) and requires emergency intervention.

Special Populations

1. H. pylori is present in nearly half the world's population, but not everyone infected develops gastritis or cancer.

2. Patients with autoimmune gastritis are likely to have other autoimmune disorders.

3. Autoimmune gastritis involves T-cell mediated destruction of parietal cells and can lead to pernicious anemia.

4. Cases of NSAID-related peptic ulcers are increasing, possibly due to an aging population relying on NSAIDs for pain relief.

5. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare cause of gastric ulcers that should be considered in refractory cases.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Advanced Management Protocols

1. First-line H. pylori therapy: 10-14 day regimens of PPI + clarithromycin + amoxicillin (CAP) or PPI + bismuth + tetracycline + metronidazole (PBMT).

2. Second-line therapy for H. pylori failures: Switch to alternative regimen or perform susceptibility testing.

3. Risk stratification for GI bleeders: Glasgow-Blatchford score and Rockall score help determine intensity of care and likelihood of rebleeding.

4. Management of NSAID-associated ulcers: COX-2 selective inhibitors with PPI prophylaxis for high-risk patients requiring continued NSAID therapy.

5. Refractory ulcers: Consider rare etiologies including Crohn's disease, malignancy, cytomegalovirus, tuberculosis, and syphilis.

Long-term Follow-up and Prevention

1. Post-H. pylori eradication: Confirm cure with urea breath test or stool antigen 4+ weeks after completing therapy and stopping PPI.

2. Surveillance recommendations for intestinal metaplasia: Endoscopic surveillance every 3 years in high-risk patients.

3. PPI risk mitigation: Long-term PPI therapy associated with increased risk of C. difficile infection, pneumonia, fractures, vitamin B12 deficiency, and hypomagnesemia.

4. Antiplatelet/anticoagulant management: Decision algorithms for stopping or continuing therapy in active ulcer bleeding based on thrombotic risk.

5. Quality metrics: Documentation of H. pylori testing after ulcer diagnosis and confirmation of eradication are established quality measures.