Testicular physiology regulates the formation of sperm cells during the reproductive years.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis regulates testicular hormone production and spermatogenesis.

We show the hypothalamus and pituitary gland (aka, hypophysis) and label the anterior lobe of the gland. We show a testicle covered by its tunics; we include the epididymis and proximal vas deferens, which delivers sperm from the testicle to the penis.

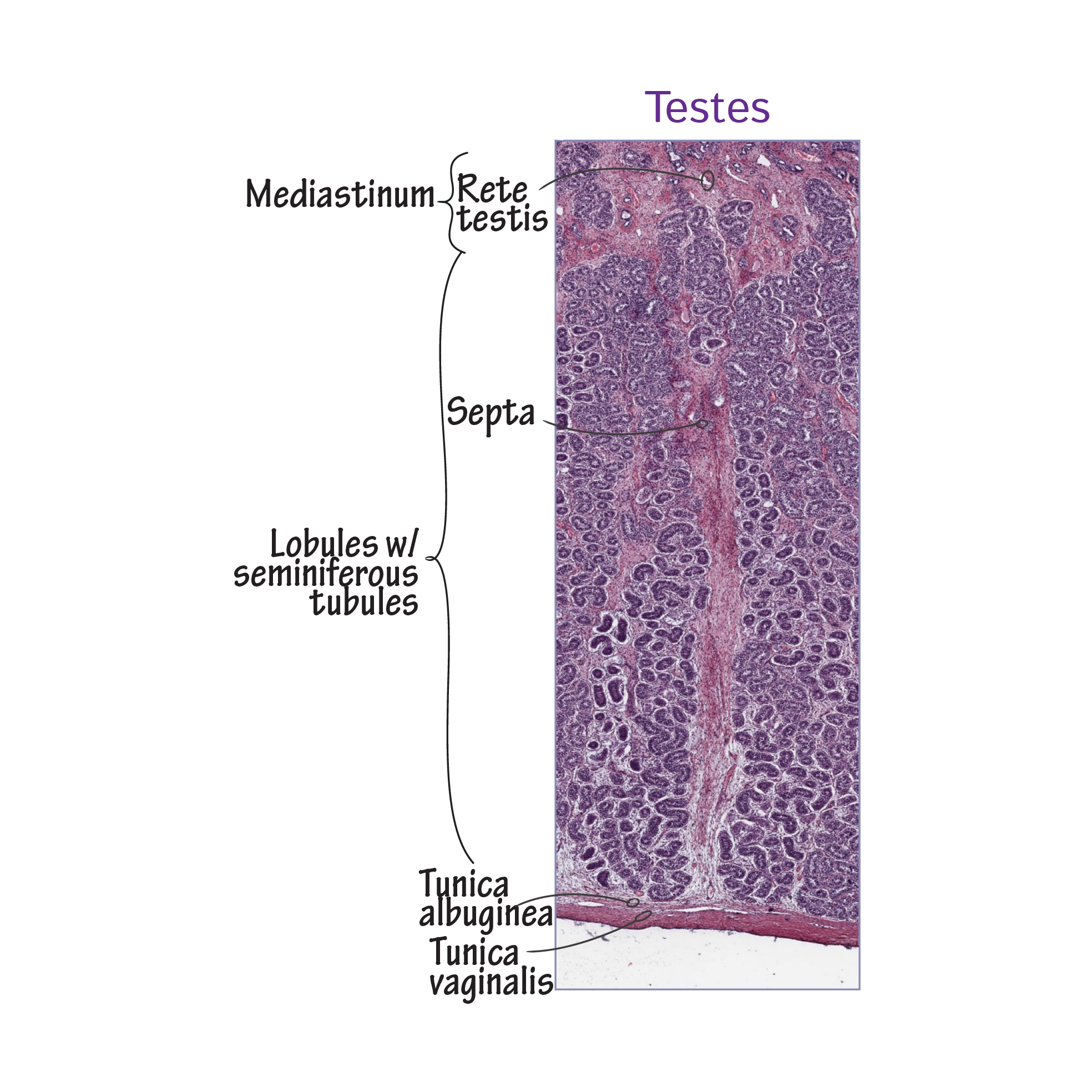

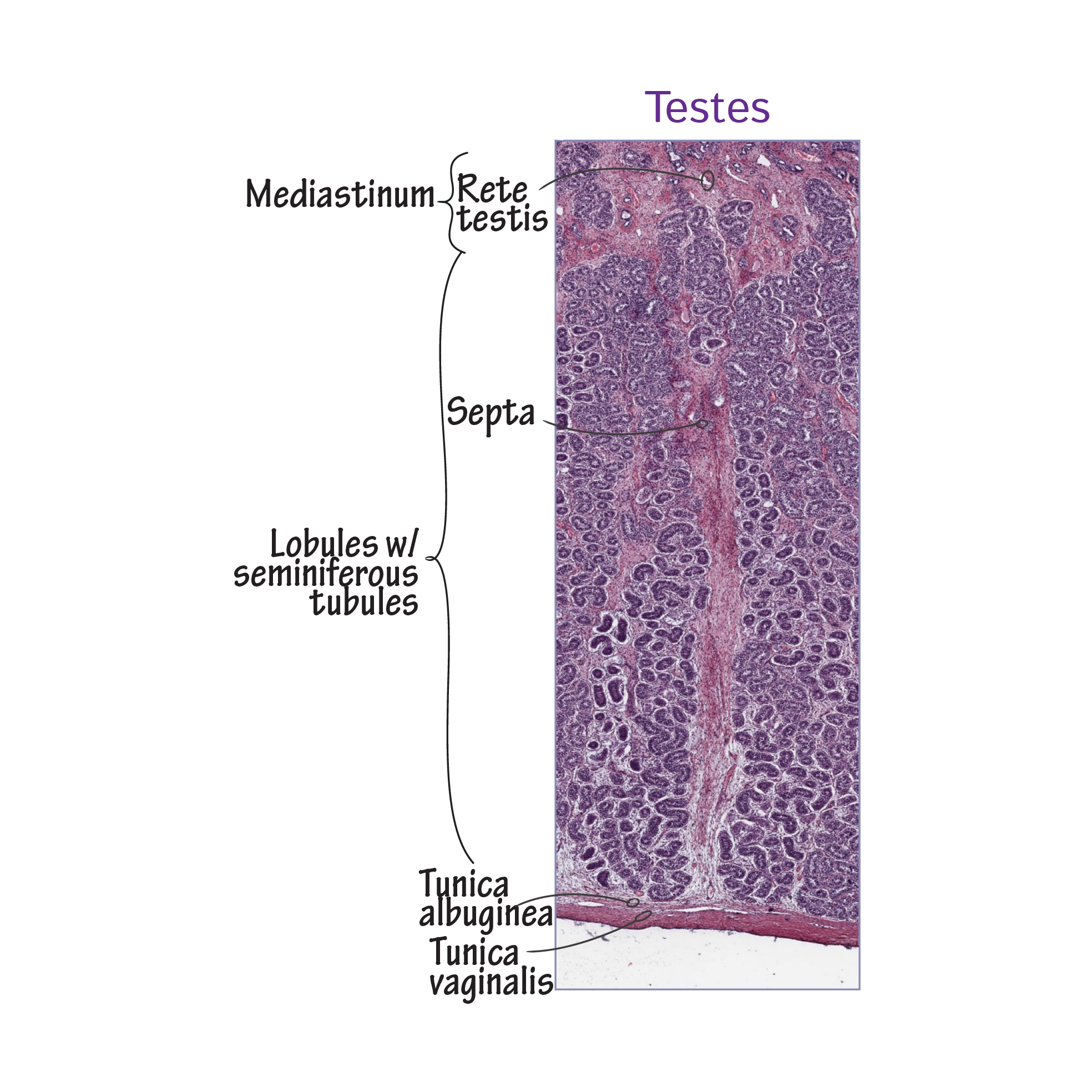

The testes comprise many tightly wound seminiferous tubules, in which hormone and sperm production occur.

So, in an expanded view, show a seminiferous tubule in cross section: show the sustentacular (aka, Sertoli) cells that "nurse" the developing spermatogonia and spermatids. We show immature sperm cells with their tails facing the lumen of the tubule.

Outside of the tubule, show an interstitial cell, aka, a Leydig cell.

The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which travels to the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland.

In response to GnRH, pituitary gonadotrophs release luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone (LH and FSH, respectively). These hormones are called gonadotropins because they act on the gonads.

LH binds interstitial cells and triggers testosterone release.

Testosterone has both endocrine and paracrine effects:

To exert its endocrine effects, testosterone leaves the testes and enters the bloodstream to have various androgenic effects.

- Increases penis, scrotum, and testes size.

- Promotes musculoskeletal density and mass.

- Stimulates hair growth and sebaceous gland activity.

- And, Enlarges the larynx (aka, "voice box"), which deepens the voice.

Testosterone has paracrine effects on spermatogenesis within the seminiferous tubules:

- Testosterone directly influences spermatogenesis and, in conjunction with FSH, stimulates the sustentacular "nurse" cells that support the developing gametes (we'll return to these cells in a moment).

Both within the testes and in the body tissues, some testosterone is converted to estradiol; within the testes, estradiol inhibits testosterone release from interstitial cells (not shown).

Furthermore, testosterone is produced in lower quantities by several other tissues, including adipose, muscle, the adrenal cortex, and the brain.

Negative feedback: Testosterone exerts negative feedback at the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary gland to inhibit the release of GnRH and LH, thus ensuring that testosterone levels remain conducive to sperm production.

Sustentacular cells "nurse" the developing gametes:

- They help physically support and protect the spermatogenic cells, and provide them with nutrients, and their fluids help with spermatozoa movement in the tubules.

- Sustentacular cells also secrete androgen-binding protein, which binds testosterone to keep its local concentration high to promote spermatogenesis.

- Sustentacular cells release inhibin, which it blocks further secretion of FSH from the anterior pituitary.

Production of testosterone is impaired, leading to reductions in spermatogenesis and systemic androgenic effects.

Primary hypogonadism: testosterone cannot be produced due to malfunctioning within the testes, themselves. Klinefelter syndrome, in which a patient has a Y chromosome and two or more X chromosomes, an example of primary hypogonadism.

Secondary hypogonadism: testosterone concentrations are low due to abnormalities arising in the hypothalamus and/or anterior pituitary, not in the testes. Kallmann's syndrome, which is due to abnormal hypothalamic development, is an example of this.

Outside of the tubule, show an interstitial cell, aka, a Leydig cell.

Outside of the tubule, show an interstitial cell, aka, a Leydig cell.