PANCE - Jaundice

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for PANCE from the Jaundice tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for PANCE.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for PANCE.

- --

VITAL FOR PANCE

Clinical Presentation & Evaluation

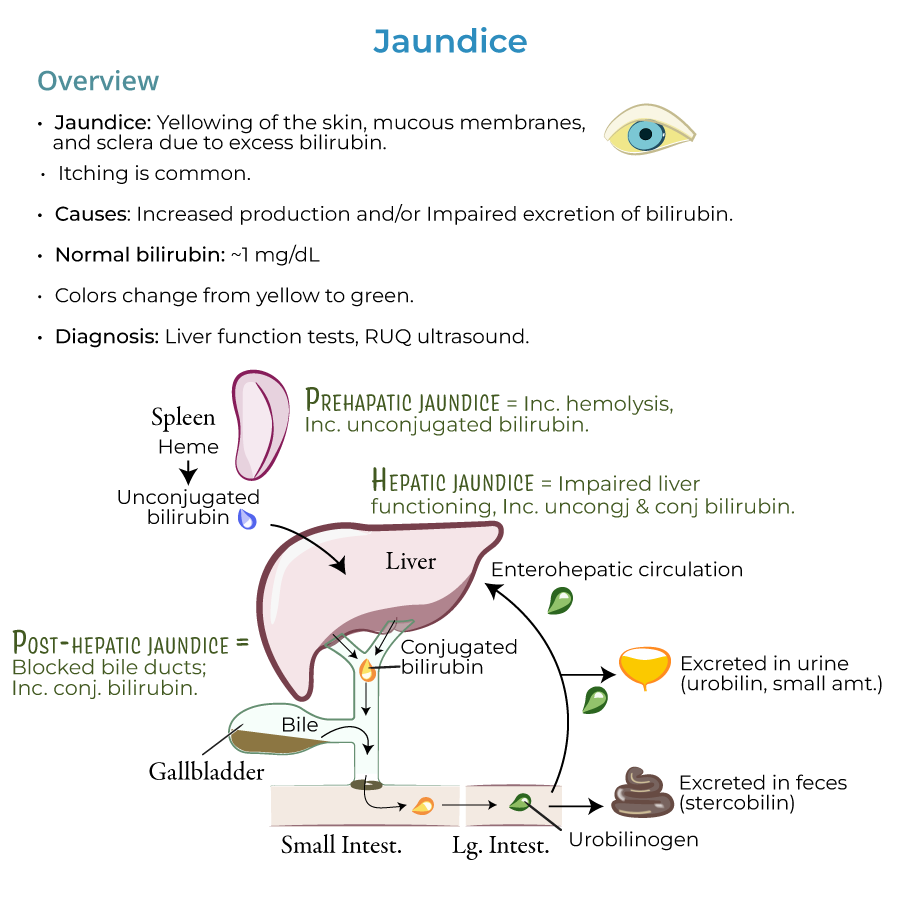

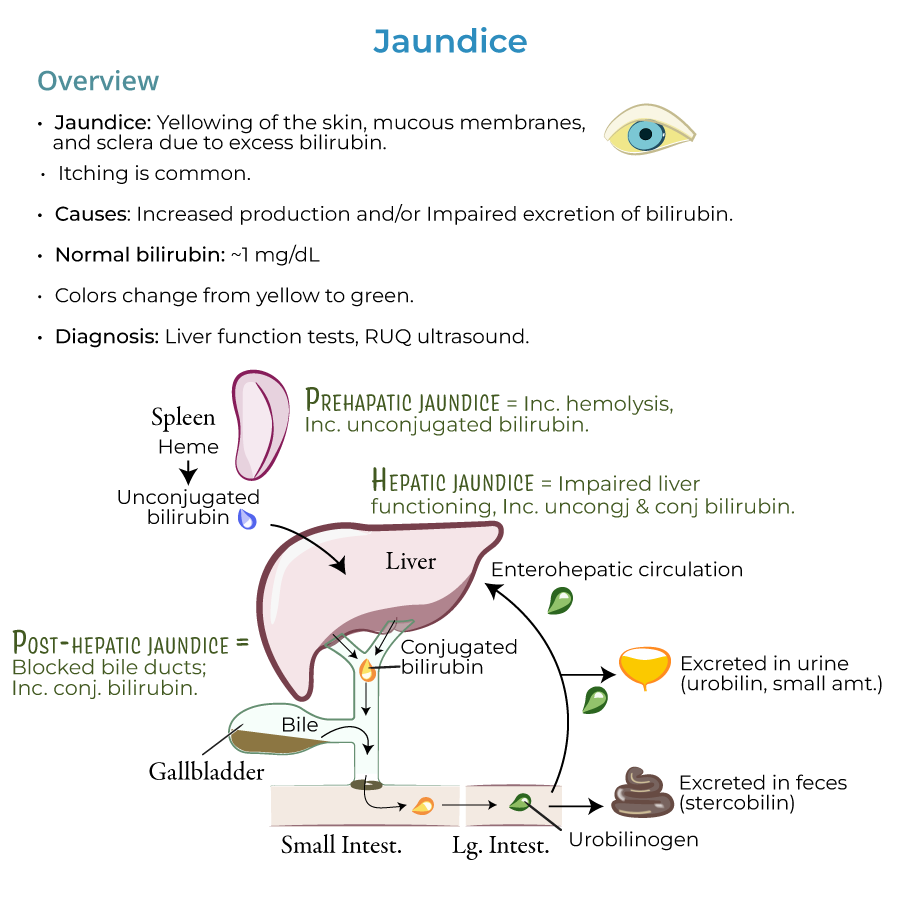

1. Definition and appearance: Jaundice presents as yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes, and sclera due to excess bilirubin; itching is also common.

2. Laboratory values: Normal bilirubin values are approximately 1 mg/dL; jaundice is usually present when levels are 2.5 mg/dL and higher.

3. Color progression: As bilirubin accumulates, jaundice can progress from a yellowish to greenish color.

4. Diagnostic approach: Jaundice is a sign of an underlying disorder, so we need to investigate its causes to find the appropriate treatment.

5. Essential workup: We use liver function tests and, when biliary obstruction is suspected, right upper quadrant ultrasound to discover and treat the origins of jaundice.

Pathophysiology Framework

1. Pre-hepatic phase: Heme converted to unconjugated bilirubin in reticuloendothelial cells, primarily in the spleen.

2. Hepatic phase: Unconjugated bilirubin travels to liver, where it's taken up by hepatocytes and conjugated.

3. Post-hepatic phase: Transfer of conjugated bilirubin in bile through the biliary system to intestines.

4. Intestinal metabolism: Bacterial enzymes in intestine reduce conjugated bilirubin to produce urobilinogens, which are excreted as stercobilin (feces) and urobilin (urine).

5. Clinical approach: HOT Liver mnemonic – Hemolysis, Obstruction, Tumors, and Liver diseases – provides framework for differential diagnosis.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Differential Diagnosis by Type

1. Indirect (unconjugated) hyperbilirubinemia:

- Key feature: Unconjugated bilirubin does not appear in urine (not water soluble)

- Pre-hepatic causes: Increased hemolysis (sickle cell anemia, G6PD deficiency), inefficient erythropoiesis (thalassemia, pernicious anemia), and increased bilirubin production (massive blood transfusions, hematoma resorption)

- Intrahepatic causes: Medications (protease inhibitors, Rifampin), Gilbert syndrome, and Crigler-Najjar syndrome

- Key feature: Excess conjugated bilirubin is water soluble and appears in urine (dark urine)

- Genetic disorders: Dubin-Johnson syndrome and Rotor syndrome

- Cholestasis (bile flow blockage): Post-hepatic causes (gallstone obstruction, biliary inflammation, ductal compression) and intrahepatic causes (cholestatic liver disease, infiltrative diseases, sepsis, pregnancy, TPN)

- Clinical sign: Pale, chalky-colored feces (absence of stercobilin)

- Key feature: Increased levels of both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin with abnormal liver function tests

- Major causes: Viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, other viral infections (Yellow fever, EBV, CMV, HSV), other disorders (cirrhosis, Wilson's disease), and drugs/toxins (estrogen, acetaminophen, arsenic)

Clinical Pearls for Diagnosis

1. Carotenemia vs. jaundice: Excess carotene can cause yellow/orange skin color, but the sclera is spared.

2. Demographics: Jaundice is most common in newborns and the elderly due to impaired conjugation in the liver and/or excretion.

3. Key laboratory findings: Direct vs. indirect hyperbilirubinemia helps narrow differential diagnosis.

4. Urine and stool changes: Dark urine suggests conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; pale stools suggest cholestasis.

5. Red flags: Jaundice with fever, severe abdominal pain, or altered mental status requires urgent evaluation.

Special Populations

1. Neonatal jaundice types: Physiologic jaundice (immature hepatic conjugation), breast milk jaundice (3-12 weeks duration), and breastfeeding jaundice (insufficient intake).

2. Neonatal complications: Newborns are particularly susceptible to kernicterus (brain damage from bilirubin deposits).

3. Pregnancy considerations: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy requires careful monitoring.

4. Geriatric patients: Higher risk for drug-induced jaundice and malignant causes of biliary obstruction.

5. Critical illness: Sepsis-associated jaundice and TPN-related cholestasis in hospitalized patients.

Management Considerations

1. Hemolytic causes: Address underlying hemolytic disorders.

2. Obstructive causes: May require intervention to relieve biliary obstruction.

3. Hepatocellular causes: Management depends on specific etiology (viral, alcoholic, autoimmune).

4. Monitoring parameters: Serial bilirubin levels, liver function tests, coagulation studies.

5. Red flags for referral: Progressive jaundice, signs of liver failure, or suspected malignancy.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Clinical Decision Making

1. History elements: Focus on medication list, alcohol use, risk factors for viral hepatitis, family history of liver or hemolytic disease, and recent exposures or travel.

2. Physical exam focus: Beyond jaundice, look for hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, spider angiomata, palmar erythema, asterixis, and stigmata of chronic liver disease.

3. Initial lab panel: CBC with peripheral smear, comprehensive metabolic panel, fractionated bilirubin, PT/INR, hepatitis serologies, and urinalysis.

4. Advanced imaging: When to progress from ultrasound to CT, MRCP, or ERCP based on clinical suspicion.

5. Consultation thresholds: When to involve gastroenterology, hepatology, or surgery in management.

Therapeutic Interventions

1. Supportive care: Fluid management, nutrition support, vitamin K for coagulopathy, antihistamines for pruritus.

2. Procedural interventions: ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction for choledocholithiasis; stenting for malignant strictures.

3. Medication management: N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen toxicity; corticosteroids for severe alcoholic or autoimmune hepatitis; ursodeoxycholic acid for primary biliary cholangitis.

4. Neonatal jaundice: Phototherapy protocols based on gestational age, age in hours, and bilirubin levels; when to consider exchange transfusion.

5. Surgical considerations: Timing of cholecystectomy in gallstone disease; surgical options for malignant obstruction.

Preventive Strategies

1. Vaccination: Hepatitis A and B vaccines for high-risk individuals and as routine prevention.

2. Screening recommendations: Appropriate hepatitis screening based on risk factors; monitoring in patients on hepatotoxic medications.

3. Alcohol counseling: Strategies for alcohol cessation in alcoholic liver disease.

4. Pregnancy monitoring: Serial bile acid and liver function tests in cholestasis of pregnancy.

5. Metabolic optimization: Management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through weight loss, diabetes control, and lipid management.

Patient Education

1. Medication guidance: Avoidance of potentially hepatotoxic medications including over-the-counter products.

2. Diet recommendations: Low-sodium diet in cirrhosis; medium-chain triglyceride supplementation in cholestasis.

3. Activity modifications: Appropriate exercise recommendations based on severity of liver disease.

4. Warning signs: Symptoms requiring urgent medical attention including increasing jaundice, mental status changes, and GI bleeding.

5. Follow-up planning: Appropriate interval for laboratory monitoring and imaging based on underlying condition.

Emerging Concepts

1. Non-invasive fibrosis assessment: Use of FibroScan, FibroTest, and other modalities to assess liver fibrosis without biopsy.

2. Genetic testing: Role of genetic panels in diagnosis of hereditary liver diseases.

3. Novel therapies: Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C; farnesoid X receptor agonists for primary biliary cholangitis and NASH.

4. Microbiome considerations: Role of intestinal flora in cholestatic conditions and potential therapeutic implications.

5. Point-of-care testing: Emerging technologies for rapid bilirubin assessment and monitoring, especially in resource-limited settings.