PANCE - Heart Murmurs

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for PANCE from the Hypertension Overview tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

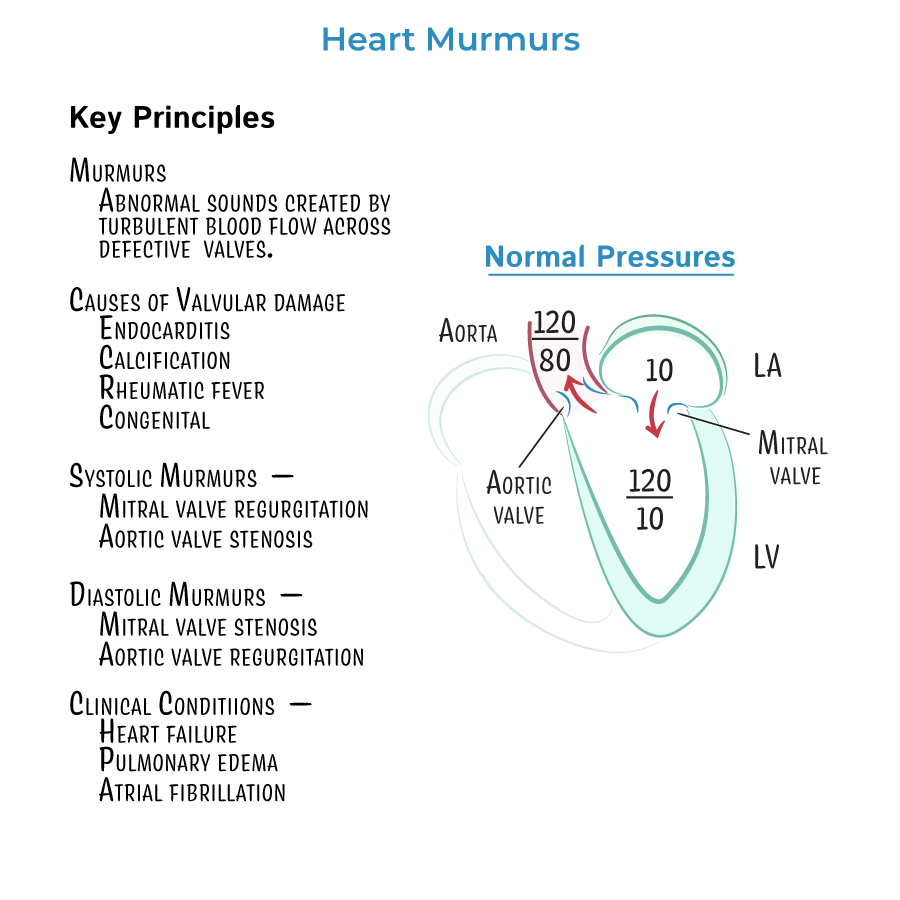

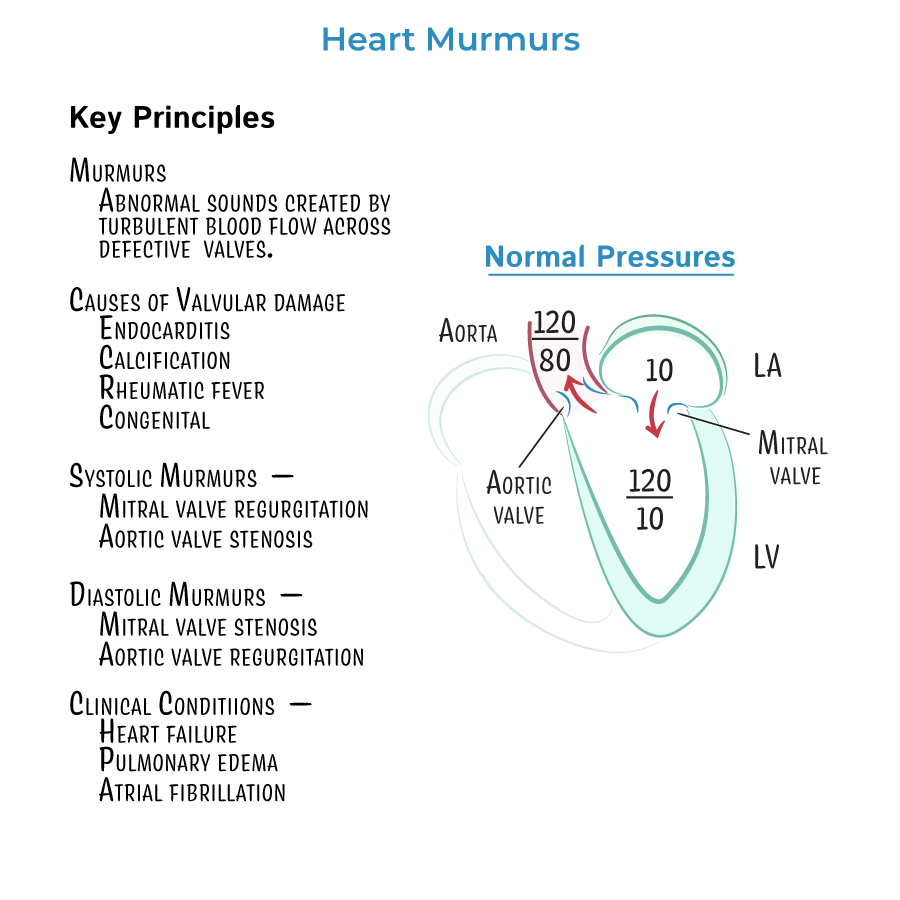

1. Heart murmurs are caused by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves, which may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (insufficiency).

2. Aortic stenosis produces a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur that is best heard at the right upper sternal border and radiates to the carotid arteries. Patients may present with the classic triad of syncope, angina, and dyspnea on exertion.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It is commonly caused by mitral valve prolapse, ischemic heart disease, or rheumatic fever.

4. Mitral valve prolapse presents with a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur. It often increases in intensity with maneuvers that decrease preload, such as Valsalva or standing.

5. Aortic regurgitation creates an early diastolic, high-pitched blowing murmur best heard at the left sternal border. It is associated with a widened pulse pressure and bounding peripheral pulses. Corrigan’s sign, or head bobbing with each heartbeat, is a classic finding.

6. Mitral stenosis is characterized by an opening snap followed by a low-pitched diastolic rumble best heard at the apex in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Common symptoms include dyspnea, orthopnea, and palpitations.

7. Murmur timing is a critical diagnostic clue. Systolic murmurs occur between S1 and S2, and include aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and mitral valve prolapse. Diastolic murmurs occur after S2 and include aortic regurgitation and mitral stenosis.

8. Tricuspid regurgitation presents similarly to mitral regurgitation but is heard best at the left lower sternal border and increases with inspiration, known as Carvallo’s sign.

9. Ventricular septal defect, a congenital lesion, produces a harsh holosystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border and is often accompanied by signs of a left-to-right shunt.

10. Patent ductus arteriosus presents with a continuous "machinery" murmur that is loudest at S2 and typically best heard at the left infraclavicular region.

11. Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice for all valvular disorders. It assesses valve structure, function, and the impact of the lesion on cardiac chambers and flow dynamics.

12. Aortic stenosis leads to pressure overload and left ventricular hypertrophy. As the disease progresses, cardiac output decreases, leading to syncope or heart failure symptoms.

13. Chronic aortic or mitral regurgitation causes volume overload and eccentric hypertrophy. Over time, this leads to left ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction.

14. Mitral stenosis leads to increased left atrial pressure and volume, resulting in atrial enlargement, which predisposes to atrial fibrillation. Patients with mitral stenosis may present with exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and palpitations.

15. Severe mitral stenosis during pregnancy can precipitate pulmonary edema due to increased plasma volume. This is a high-risk scenario that requires close monitoring.

1. Rheumatic fever is the most common cause of mitral stenosis and can also contribute to mitral regurgitation or aortic valve disease.

2. Calcific degeneration is a leading cause of aortic stenosis in older adults, particularly those over 65 years of age.

3. Infective endocarditis may cause acute regurgitation of mitral or aortic valves, especially in individuals with preexisting valve disease or prosthetic valves. It presents with fever, a new murmur, and sometimes signs of embolism.

4. Maneuvers such as Valsalva, standing, squatting, and handgrip can help distinguish between murmurs. For example, murmurs of mitral valve prolapse and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy become louder with Valsalva, while most others become softer.

5. Chronic aortic regurgitation often presents with signs of hyperdynamic circulation, such as a bounding pulse, water-hammer pulse, and widened pulse pressure.

6. Systolic murmurs such as those in aortic stenosis often radiate to the carotids, whereas regurgitant murmurs such as mitral regurgitation radiate toward the axilla.

7. Patients with chronic mitral or aortic valve disease should undergo periodic echocardiographic monitoring to assess for progression of disease and left ventricular function.

8. Treatment of valvular disease depends on severity and symptoms. For severe stenosis or regurgitation with symptoms or evidence of ventricular dysfunction, surgical repair or valve replacement may be indicated.

9. Patients with atrial fibrillation secondary to mitral stenosis often require anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic events.

10. Medical therapy for valvular regurgitation includes afterload reduction with ACE inhibitors or vasodilators, which can improve symptoms and delay the need for surgery.

1. In patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis, surgery is generally recommended regardless of ejection fraction.

2. Mechanical valves require lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin and regular INR monitoring, whereas bioprosthetic valves may not.

3. Early signs of decompensation in valvular disease include exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, peripheral edema, and new-onset arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

4. Prophylaxis for infective endocarditis is indicated before certain dental and surgical procedures in high-risk patients, including those with prosthetic valves or a history of endocarditis.

5. Heart failure is a common final pathway of decompensated valvular disease and requires comprehensive management including fluid control, rate control, and evaluation for valve intervention.

1. Heart murmurs are caused by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves, which may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (insufficiency).

2. Aortic stenosis produces a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur that is best heard at the right upper sternal border and radiates to the carotid arteries. Patients may present with the classic triad of syncope, angina, and dyspnea on exertion.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It is commonly caused by mitral valve prolapse, ischemic heart disease, or rheumatic fever.

4. Mitral valve prolapse presents with a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur. It often increases in intensity with maneuvers that decrease preload, such as Valsalva or standing.

5. Aortic regurgitation creates an early diastolic, high-pitched blowing murmur best heard at the left sternal border. It is associated with a widened pulse pressure and bounding peripheral pulses. Corrigan’s sign, or head bobbing with each heartbeat, is a classic finding.

6. Mitral stenosis is characterized by an opening snap followed by a low-pitched diastolic rumble best heard at the apex in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Common symptoms include dyspnea, orthopnea, and palpitations.

7. Murmur timing is a critical diagnostic clue. Systolic murmurs occur between S1 and S2, and include aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and mitral valve prolapse. Diastolic murmurs occur after S2 and include aortic regurgitation and mitral stenosis.

8. Tricuspid regurgitation presents similarly to mitral regurgitation but is heard best at the left lower sternal border and increases with inspiration, known as Carvallo’s sign.

9. Ventricular septal defect, a congenital lesion, produces a harsh holosystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border and is often accompanied by signs of a left-to-right shunt.

10. Patent ductus arteriosus presents with a continuous "machinery" murmur that is loudest at S2 and typically best heard at the left infraclavicular region.

11. Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice for all valvular disorders. It assesses valve structure, function, and the impact of the lesion on cardiac chambers and flow dynamics.

12. Aortic stenosis leads to pressure overload and left ventricular hypertrophy. As the disease progresses, cardiac output decreases, leading to syncope or heart failure symptoms.

13. Chronic aortic or mitral regurgitation causes volume overload and eccentric hypertrophy. Over time, this leads to left ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction.

14. Mitral stenosis leads to increased left atrial pressure and volume, resulting in atrial enlargement, which predisposes to atrial fibrillation. Patients with mitral stenosis may present with exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and palpitations.

15. Severe mitral stenosis during pregnancy can precipitate pulmonary edema due to increased plasma volume. This is a high-risk scenario that requires close monitoring.

1. Rheumatic fever is the most common cause of mitral stenosis and can also contribute to mitral regurgitation or aortic valve disease.

2. Calcific degeneration is a leading cause of aortic stenosis in older adults, particularly those over 65 years of age.

3. Infective endocarditis may cause acute regurgitation of mitral or aortic valves, especially in individuals with preexisting valve disease or prosthetic valves. It presents with fever, a new murmur, and sometimes signs of embolism.

4. Maneuvers such as Valsalva, standing, squatting, and handgrip can help distinguish between murmurs. For example, murmurs of mitral valve prolapse and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy become louder with Valsalva, while most others become softer.

5. Chronic aortic regurgitation often presents with signs of hyperdynamic circulation, such as a bounding pulse, water-hammer pulse, and widened pulse pressure.

6. Systolic murmurs such as those in aortic stenosis often radiate to the carotids, whereas regurgitant murmurs such as mitral regurgitation radiate toward the axilla.

7. Patients with chronic mitral or aortic valve disease should undergo periodic echocardiographic monitoring to assess for progression of disease and left ventricular function.

8. Treatment of valvular disease depends on severity and symptoms. For severe stenosis or regurgitation with symptoms or evidence of ventricular dysfunction, surgical repair or valve replacement may be indicated.

9. Patients with atrial fibrillation secondary to mitral stenosis often require anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic events.

10. Medical therapy for valvular regurgitation includes afterload reduction with ACE inhibitors or vasodilators, which can improve symptoms and delay the need for surgery.

1. In patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis, surgery is generally recommended regardless of ejection fraction.

2. Mechanical valves require lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin and regular INR monitoring, whereas bioprosthetic valves may not.

3. Early signs of decompensation in valvular disease include exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, peripheral edema, and new-onset arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

4. Prophylaxis for infective endocarditis is indicated before certain dental and surgical procedures in high-risk patients, including those with prosthetic valves or a history of endocarditis.

5. Heart failure is a common final pathway of decompensated valvular disease and requires comprehensive management including fluid control, rate control, and evaluation for valve intervention.

- --

VITAL FOR PANCE

1. Heart murmurs are caused by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves, which may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (insufficiency).

2. Aortic stenosis produces a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur that is best heard at the right upper sternal border and radiates to the carotid arteries. Patients may present with the classic triad of syncope, angina, and dyspnea on exertion.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It is commonly caused by mitral valve prolapse, ischemic heart disease, or rheumatic fever.

4. Mitral valve prolapse presents with a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur. It often increases in intensity with maneuvers that decrease preload, such as Valsalva or standing.

5. Aortic regurgitation creates an early diastolic, high-pitched blowing murmur best heard at the left sternal border. It is associated with a widened pulse pressure and bounding peripheral pulses. Corrigan’s sign, or head bobbing with each heartbeat, is a classic finding.

6. Mitral stenosis is characterized by an opening snap followed by a low-pitched diastolic rumble best heard at the apex in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Common symptoms include dyspnea, orthopnea, and palpitations.

7. Murmur timing is a critical diagnostic clue. Systolic murmurs occur between S1 and S2, and include aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and mitral valve prolapse. Diastolic murmurs occur after S2 and include aortic regurgitation and mitral stenosis.

8. Tricuspid regurgitation presents similarly to mitral regurgitation but is heard best at the left lower sternal border and increases with inspiration, known as Carvallo’s sign.

9. Ventricular septal defect, a congenital lesion, produces a harsh holosystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border and is often accompanied by signs of a left-to-right shunt.

10. Patent ductus arteriosus presents with a continuous "machinery" murmur that is loudest at S2 and typically best heard at the left infraclavicular region.

11. Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice for all valvular disorders. It assesses valve structure, function, and the impact of the lesion on cardiac chambers and flow dynamics.

12. Aortic stenosis leads to pressure overload and left ventricular hypertrophy. As the disease progresses, cardiac output decreases, leading to syncope or heart failure symptoms.

13. Chronic aortic or mitral regurgitation causes volume overload and eccentric hypertrophy. Over time, this leads to left ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction.

14. Mitral stenosis leads to increased left atrial pressure and volume, resulting in atrial enlargement, which predisposes to atrial fibrillation. Patients with mitral stenosis may present with exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and palpitations.

15. Severe mitral stenosis during pregnancy can precipitate pulmonary edema due to increased plasma volume. This is a high-risk scenario that requires close monitoring.

1. Heart murmurs are caused by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves, which may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (insufficiency).

2. Aortic stenosis produces a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur that is best heard at the right upper sternal border and radiates to the carotid arteries. Patients may present with the classic triad of syncope, angina, and dyspnea on exertion.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It is commonly caused by mitral valve prolapse, ischemic heart disease, or rheumatic fever.

4. Mitral valve prolapse presents with a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur. It often increases in intensity with maneuvers that decrease preload, such as Valsalva or standing.

5. Aortic regurgitation creates an early diastolic, high-pitched blowing murmur best heard at the left sternal border. It is associated with a widened pulse pressure and bounding peripheral pulses. Corrigan’s sign, or head bobbing with each heartbeat, is a classic finding.

6. Mitral stenosis is characterized by an opening snap followed by a low-pitched diastolic rumble best heard at the apex in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Common symptoms include dyspnea, orthopnea, and palpitations.

7. Murmur timing is a critical diagnostic clue. Systolic murmurs occur between S1 and S2, and include aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and mitral valve prolapse. Diastolic murmurs occur after S2 and include aortic regurgitation and mitral stenosis.

8. Tricuspid regurgitation presents similarly to mitral regurgitation but is heard best at the left lower sternal border and increases with inspiration, known as Carvallo’s sign.

9. Ventricular septal defect, a congenital lesion, produces a harsh holosystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border and is often accompanied by signs of a left-to-right shunt.

10. Patent ductus arteriosus presents with a continuous "machinery" murmur that is loudest at S2 and typically best heard at the left infraclavicular region.

11. Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice for all valvular disorders. It assesses valve structure, function, and the impact of the lesion on cardiac chambers and flow dynamics.

12. Aortic stenosis leads to pressure overload and left ventricular hypertrophy. As the disease progresses, cardiac output decreases, leading to syncope or heart failure symptoms.

13. Chronic aortic or mitral regurgitation causes volume overload and eccentric hypertrophy. Over time, this leads to left ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction.

14. Mitral stenosis leads to increased left atrial pressure and volume, resulting in atrial enlargement, which predisposes to atrial fibrillation. Patients with mitral stenosis may present with exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and palpitations.

15. Severe mitral stenosis during pregnancy can precipitate pulmonary edema due to increased plasma volume. This is a high-risk scenario that requires close monitoring.

- --

HIGH YIELD

- --

Beyond the Tutorial