ABIM - Myocardial Infarction

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Examination from the Myocardial Infarctions: Diagnosis & Treatment tutorial, focusing on clinical management and treatment decision-making that are essential for board certification. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

3. Cardiac biomarkers:

3. Cardiac biomarkers:

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for the American Board of Internal Medicine Examination.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for the American Board of Internal Medicine Examination.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

Epidemiology & Disparities in Care

1. Evolving trends: Incidence of myocardial infarctions is declining in high-income countries but rising in middle- and low-income countries.

2. Demographic variations: Incidence after age 35, from highest to lowest: Black males > Black females > White males > White females.

3. Gender differences: MI occurs approximately 10 years earlier in men than women, possibly related to risk factors like smoking and hyperlipidemia.

4. Mortality patterns: Although overall mortality has declined, rates remain higher in women than men, especially for young and minority women.

5. Disease progression: Myocardial infarction is an important cause of heart failure, which is itself a significant cause of death.

Risk Assessment & Prevention

1. Major modifiable risk factors: Dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking (including e-cigarettes), obesity, psychosocial stress, alcohol consumption, poor diet (low in fruits and vegetables).

2. Patient awareness challenges: Many patients, especially women, are unaware of risk factors and symptoms—a significant obstacle to prevention and treatment.

3. Pre-infarction symptoms: Prodromal symptoms may occur days, weeks, or even months prior to the actual heart attack.

4. Risk factor management: Long-term treatment focuses on reducing risk factors through improved diet, exercise, and medications for hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

5. Special populations: Understanding demographic-specific clinical presentations improves risk assessment and management.

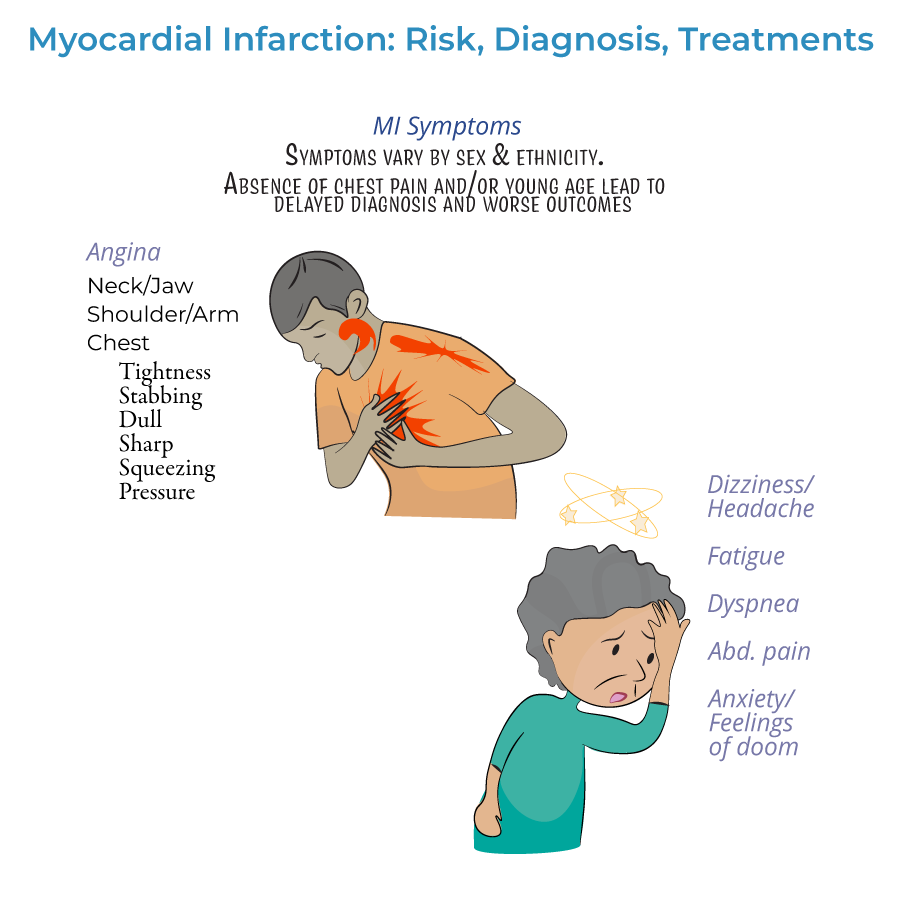

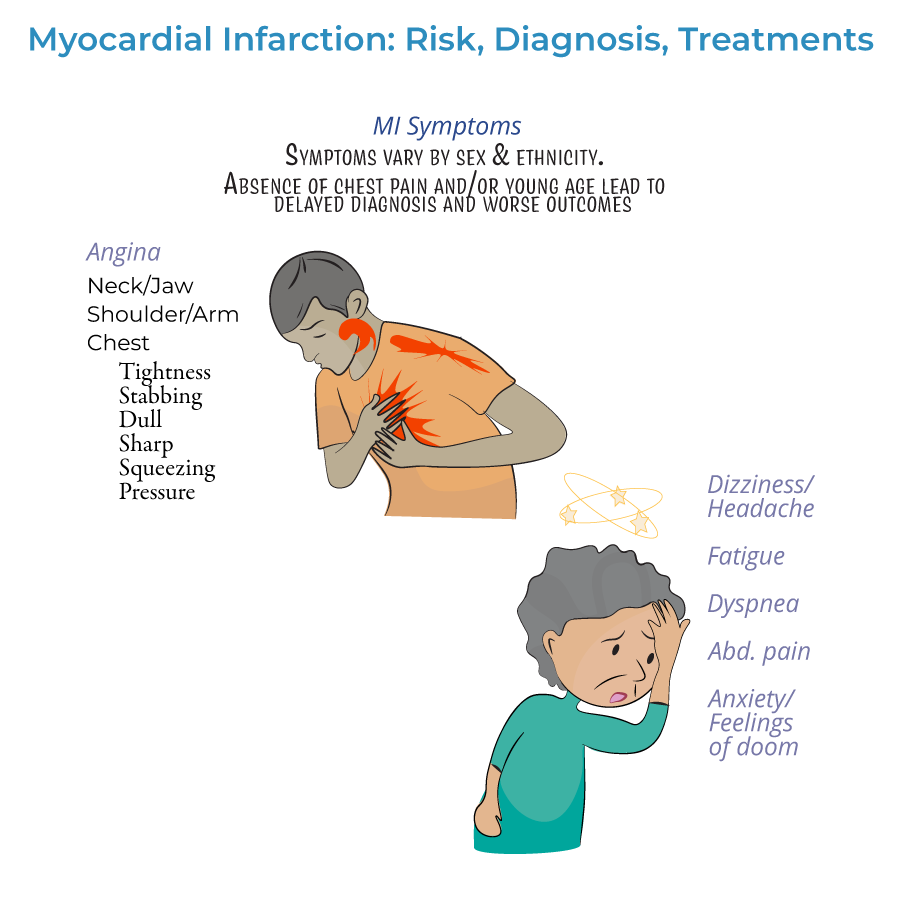

Clinical Presentation & Evaluation

1. Diagnostic definition: Myocardial infarction is defined as myocardial injury with ischemia.

2. Presentation spectrum:

- Typical symptoms: Chest pain/angina (dull, sharp, squeezing, pressure, or discomfort) radiating to arms, neck, jaw, or back

- Atypical presentations: Common in women, elderly, and diabetics

- Silent MI: No noticeable symptoms

Diagnostic Approach

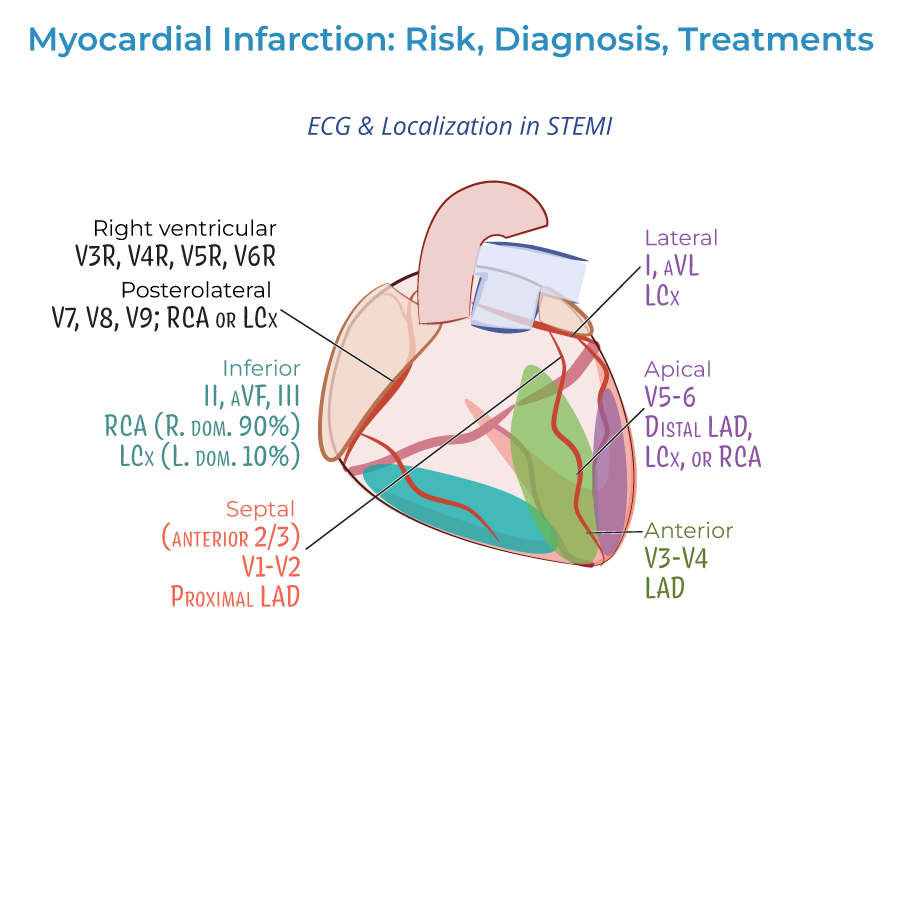

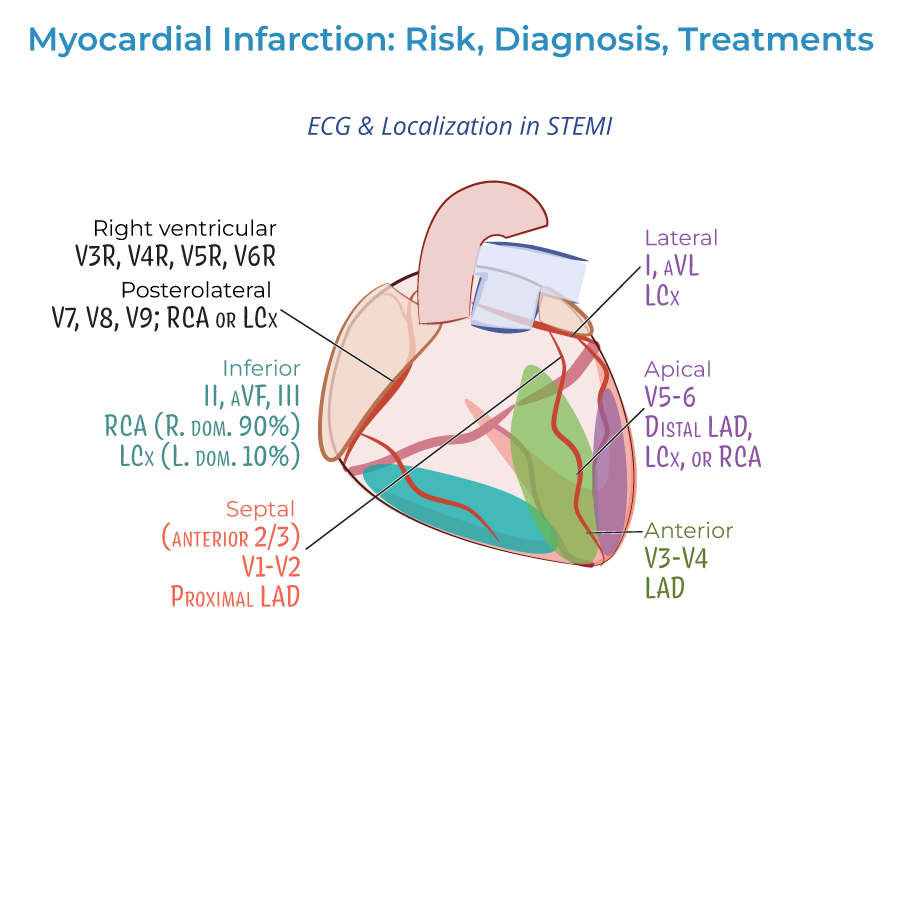

1. ECG interpretation:

- Should be obtained as soon as possible when MI is suspected

- Distinguishes between STEMI and NSTEMI, which influences treatment strategies

- Should be repeated frequently to observe the evolution of the infarction

- Q-wave abnormalities may indicate size/location of current MI or evidence of prior MI

- Lateral infarction: Leads I and aVL; left circumflex artery

- Apical infarction: Leads V5 and V6; left circumflex or right coronary arteries

- Anterior infarction: Leads V3 and V4; left anterior descending artery

- Anterior septal infarction: Leads V1 and V2; proximal left anterior descending artery

- Inferior infarction: Leads II, aVF, and III; right coronary artery or left circumflex artery

- Right ventricular infarction: Requires additional leads V3R through V6R

- Posterolateral infarction: Requires additional leads V7-V9; right coronary or left circumflex artery

3. Cardiac biomarkers:

3. Cardiac biomarkers:

- Essential for diagnosis, especially cardiac troponin

- Help distinguish between NSTEMI and unstable angina

- Both troponin I and CK-MB peak within 24 hours of the MI and fall to normal levels over time

Treatment Approach

1. Timing principles: Treatment should begin as soon as possible, ideally even before hospital arrival, to reduce the extent of myocardial necrosis.

2. Pre-hospital management:

- Oxygen administration when oxygen saturation is less than 90%

- Aspirin for antiplatelet effects

- Nitrates for chest pain (morphine is an option if nitrates are ineffective)

- Vary by severity of infarction

- Include percutaneous coronary intervention (angioplasty), coronary bypass grafting, or fibrinolytic drugs

- STEMI patients should receive emergency PCI; if unavailable, fibrinolytic drugs must be given as soon as possible

- Unstable, complicated NSTEMI often requires immediate PCI or CABG

- Uncomplicated NSTEMI patients may wait longer, and revascularization may not be necessary

- Fibrinolytic drugs generally not recommended for NSTEMI (risks outweigh benefits)

- Antiplatelets (aspirin, clopidogrel, or others)

- Anticoagulation drugs (unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin)

- Beta-blockers (or calcium-channel blockers)

- Statins

- ACE-inhibitors

- --

HIGH YIELD

Detailed Clinical Presentations

1. Symptom variability: Chest pain or angina is variably described as dull, sharp, squeezing, pressure, or simply discomfort—understanding this spectrum improves recognition.

2. Pain radiation patterns: May radiate from the chest to arms, neck, jaw, or back—radiation patterns can help confirm diagnosis.

3. Non-chest pain presentations: Not all patients experience angina; absence increases risk of missed diagnosis, especially in women and elderly.

4. Prodromal symptoms: May occur days, weeks, or even months before the acute event—recognition can enable earlier intervention.

5. Psychological manifestations: Anxiety or sense of impending doom may precede or accompany MI—should not be dismissed as purely psychiatric.

ECG Interpretation Pearls

1. Serial assessment: ECGs should be repeated frequently to observe the evolution of infarction patterns.

2. STEMI vs. NSTEMI distinction: Critical for determining appropriate reperfusion strategy.

3. Localization significance: Different lead changes indicate specific coronary artery territories:

- Anterior (V3-V4): Left anterior descending artery

- Anteroseptal (V1-V2): Proximal left anterior descending artery

- Lateral (I, aVL): Left circumflex artery

- Apical (V5-V6): Left circumflex or right coronary arteries

- Inferior (II, III, aVF): Right coronary artery (or less frequently left circumflex)

Biomarker Interpretation

1. Diagnostic utility: Cardiac biomarkers, especially troponin, are key to diagnosing myocardial infarction.

2. Differential diagnosis: Biomarker values help distinguish between NSTEMI and unstable angina—only NSTEMI shows rising/falling troponin.

3. Temporal patterns: Both cardiac troponin I and CK-MB peak within 24 hours of MI and gradually return to normal.

4. Sampling protocols: Serial measurements provide more diagnostic value than single determinations.

5. Integration with clinical findings: Biomarkers should be interpreted in the context of symptoms and ECG findings.

Reperfusion Decision-Making

1. STEMI management: Emergency PCI recommended; if unavailable, fibrinolytic drugs must be given as soon as possible.

2. NSTEMI approach: Timing of intervention based on risk stratification:

- Unstable/complicated cases: Immediate PCI/CABG

- Uncomplicated cases: May wait longer; revascularization may not be necessary

Special Populations Considerations

1. Gender differences: Women experience MI approximately 10 years later than men, often with atypical symptoms, and have higher mortality rates.

2. Racial/ethnic variations: Significant differences in MI incidence across populations, with Black males having highest incidence after age 35.

3. Young patients: Absence of chest pain and young age often leads to missed diagnosis—maintain high index of suspicion.

4. Awareness disparities: Many patients, especially women, are unaware of risk factors and symptoms—patient education is crucial.

5. Risk factor clustering: Combinations of risk factors like smoking, dyslipidemia, and diabetes significantly increase MI risk.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Advanced Risk Stratification

1. TIMI Risk Score: Predicts 14-day and 1-year mortality risk in STEMI/NSTEMI patients.

2. GRACE Risk Score: Predicts in-hospital and 6-month mortality for ACS patients.

3. HEART Score: Stratifies chest pain patients in the emergency department for early discharge consideration.

4. Bleeding risk assessment: CRUSADE score for NSTEMI and HAS-BLED for anticoagulated patients.

5. Long-term risk prediction: ASCVD risk calculator for secondary prevention intensity.

Contemporary Management Strategies

1. Pharmaco-invasive approach: Pre-hospital fibrinolysis followed by early angiography in certain settings.

2. P2Y12 inhibitor selection: Clopidogrel vs. ticagrelor vs. prasugrel based on patient characteristics.

3. Anticoagulant options: UFH, LMWH, fondaparinux, or bivalirudin based on clinical scenario.

4. Complete vs. culprit-only revascularization: Strategies for multivessel disease in STEMI.

5. Optimal timing of non-culprit lesion intervention: Immediate vs. staged approach.

Complications Management

1. Mechanical complications: Recognition and management of papillary muscle rupture, ventricular septal defect, and free wall rupture.

2. Cardiogenic shock: Early recognition, hemodynamic support, and revascularization strategies.

3. Post-MI arrhythmias: Acute management and long-term risk stratification.

4. Right ventricular infarction: Special management considerations including volume resuscitation.

5. Post-infarction pericarditis: Differentiation from reinfarction and appropriate therapy.

Secondary Prevention and Follow-up

1. Optimal medical therapy: Evidence-based medication regimens and dosing.

2. Cardiac rehabilitation: Structured programs to improve outcomes and reduce readmissions.

3. Implantable device considerations: ICD and CRT evaluations post-MI.

4. Return to activities: Evidence-based guidance for driving, physical activity, and work.

5. Long-term monitoring: Appropriate use of testing for residual ischemia and ventricular function assessment.

Quality and Systems-Based Practice

1. Core quality metrics: Door-to-ECG time, door-to-needle time, door-to-balloon time.

2. Regional STEMI systems: Network organization and transfer protocols.

3. Discharge planning: Medication reconciliation, follow-up arrangements, and transition of care.

4. Readmission reduction: Evidence-based strategies to prevent 30-day readmissions.

5. Healthcare disparities: Recognition and addressing gaps in MI care and outcomes.