ABIM - Jaundice

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for ABIM from the Jaundice tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

Clinical Presentation & Pathophysiology

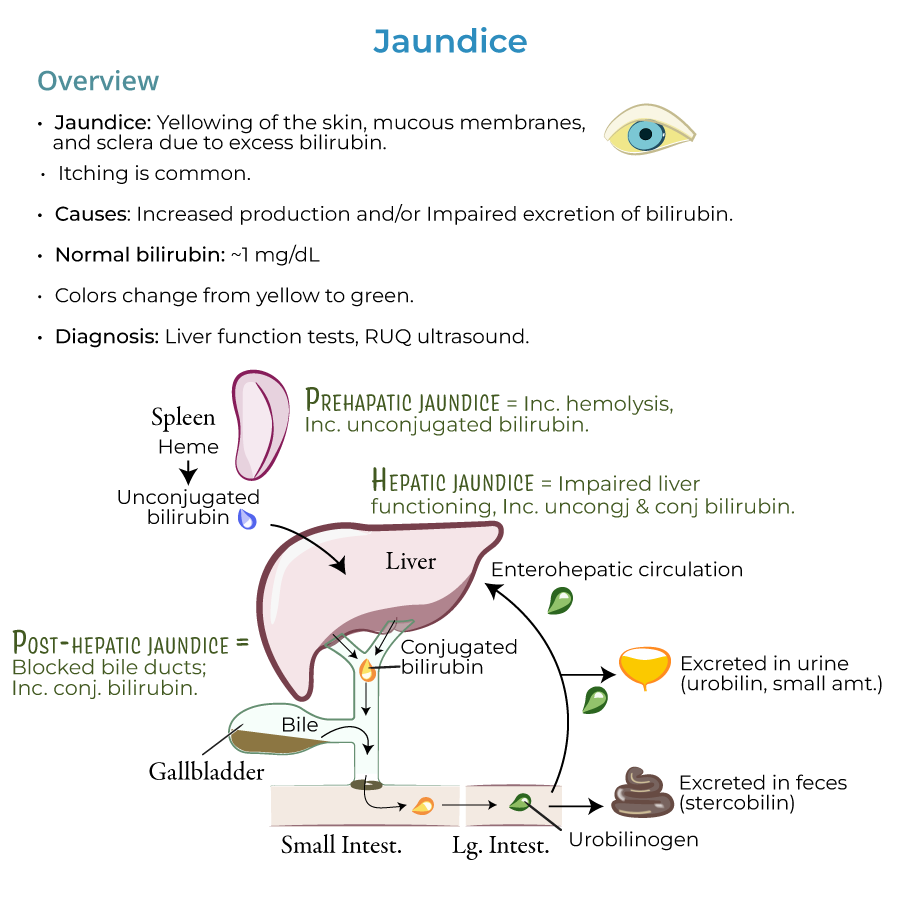

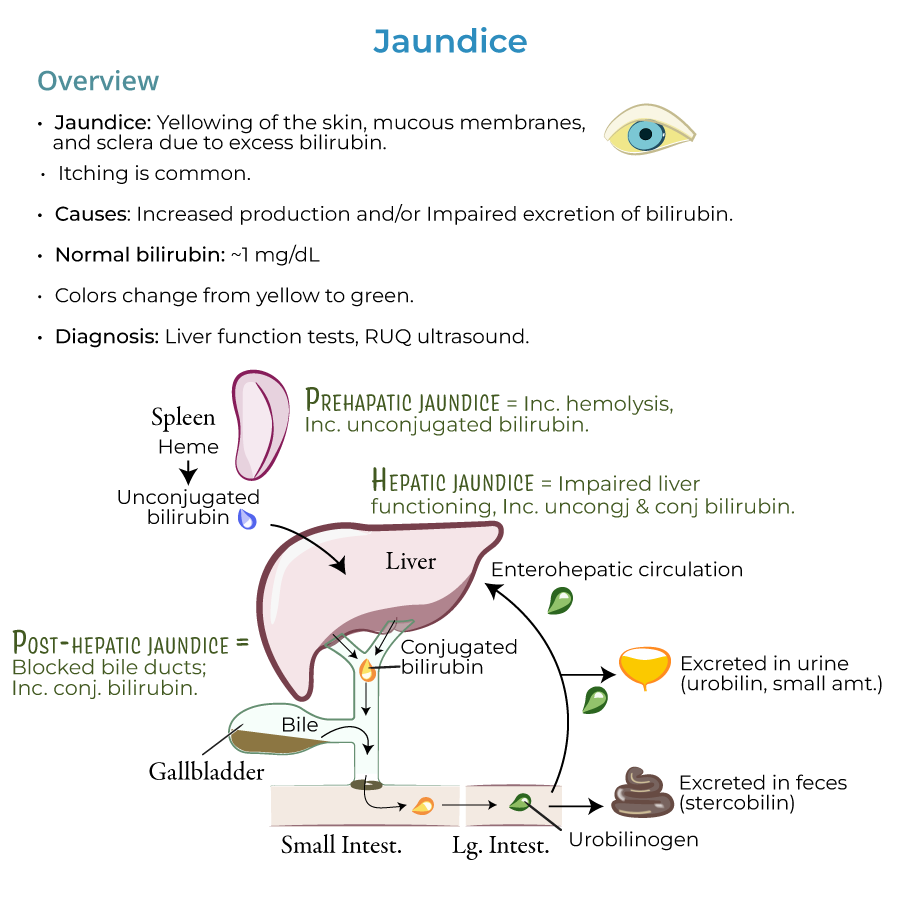

1. Definition: Jaundice presents as yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes, and sclera due to excess bilirubin; itching is also common.

2. Bilirubin metabolism: Bilirubin is a pigment in the bile; it is a by-product of heme degradation.

3. Diagnostic thresholds: Normal bilirubin values are approximately 1 mg/dL; jaundice is usually present when levels are 2.5 mg/dL and higher.

4. Progression: As bilirubin accumulates, jaundice can progress from a yellowish to greenish color.

5. Differential features: Excess carotene can cause yellow/orange skin color, but the sclera is spared (important diagnostic distinction).

Pathophysiologic Framework

1. Pre-hepatic phase: Heme is converted to unconjugated bilirubin in reticuloendothelial cells, primarily in the spleen (also in bone marrow and liver).

2. Hepatic phase: Unconjugated bilirubin travels to the liver, where it is taken up by hepatocytes and conjugated.

3. Post-hepatic phase: Transfer of conjugated bilirubin in bile through the biliary system to intestines where bacterial enzymes reduce it to urobilinogen.

4. Excretion pathways: Most urobilinogen is excreted in feces as stercobilin (gives feces brown color); small portion excreted in urine as urobilin.

5. Enterohepatic circulation: Some urobilinogen is recycled back to the liver.

Clinical Approach to Diagnosis

1. Diagnostic framework: Jaundice is a sign of an underlying disorder requiring investigation of causes to determine appropriate treatment.

2. Essential workup: Liver function tests and right upper quadrant ultrasound (when biliary obstruction is suspected) are key diagnostic tools.

3. Clinical categorization: HOT Liver mnemonic – Hemolysis, Obstruction, Tumors, and Liver diseases – provides framework for differential diagnosis.

4. High-risk populations: Jaundice is most common in newborns and the elderly due to impaired conjugation and/or excretion.

5. Key clinical signs: Dark urine indicates conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; pale, chalky-colored stools indicate cholestasis.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Bilirubin Fractions and Clinical Correlations

1. Indirect (unconjugated) hyperbilirubinemia:

- Characterized by elevated levels of unconjugated bilirubin that does not appear in urine (not water soluble)

- Pre-hepatic causes: Increased hemolysis (sickle cell anemia, G6PD deficiency), inefficient erythropoiesis (thalassemia, pernicious anemia), increased bilirubin production (massive blood transfusions, hematoma resorption)

- Intrahepatic causes: Medications (protease inhibitors, Rifampin), Gilbert syndrome, Crigler-Najjar syndrome (risk of kernicterus)

- Characterized by elevated levels of conjugated bilirubin that is water soluble and appears in urine

- Genetic disorders: Dubin-Johnson syndrome (defects in bilirubin secretion), Rotor syndrome (defects in bile storage)

- Post-hepatic causes: Gallstone obstruction, biliary inflammation/atresia/strictures, ductal compression from tumors or pancreatitis

- Intrahepatic causes: Cholestatic liver disease, infiltrative diseases (amyloidosis, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis), sepsis, pregnancy, total parenteral nutrition, malaria

- Characterized by increased levels of both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin with abnormal liver function tests

- Major causes: Hepatitis (viral, alcoholic, autoimmune, NASH), other viral infections (Yellow fever, EBV, CMV, HSV), cirrhosis, Wilson's disease, drugs/toxins (estrogen, acetaminophen, arsenic)

Specific Disease Entities

1. Cholestasis: Partial or complete blockage of bile flow; a top cause of jaundice with pale, chalky-colored feces.

2. Genetic disorders:

- Gilbert syndrome: Mild, intermittent symptoms (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase deficiency)

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome: Type 1 has total lack of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase with risk of kernicterus

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome: Often asymptomatic, defects in bilirubin secretion

- Rotor syndrome: Generally benign and self-limiting, defects in bile storage

Special Populations

1. Pregnancy-associated: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy requires careful monitoring.

2. Critically ill patients: Sepsis-associated jaundice requires identification and management.

3. Patients on TPN: Total parenteral nutrition can cause intrahepatic cholestasis.

4. Neonatal jaundice types: Physiologic jaundice (immature hepatic conjugation), breast milk jaundice (3-12 weeks), and breastfeeding jaundice (insufficient intake).

5. Patients with hemolytic disorders: Increased hemolysis is a top cause of jaundice requiring specific management.

Management Principles

1. Diagnostic algorithm: Fractionated bilirubin and pattern of liver enzyme elevation guide further workup.

2. Hepatocellular pattern: Elevated transaminases with viral serology, autoimmune markers, and toxicology screen.

3. Cholestatic pattern: Elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT with imaging to evaluate biliary system.

4. Mixed pattern: Comprehensive evaluation for complex liver diseases.

5. Complication monitoring: Patients with prolonged jaundice require monitoring for complications including coagulopathy, encephalopathy, and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Advanced Diagnostic Evaluation

1. Laboratory assessment: Beyond basic LFTs, consider ceruloplasmin, iron studies, alpha-1 antitrypsin, AMA, ASMA, immunoglobulins, and viral hepatitis serologies including quantitative PCR.

2. Imaging progression: After ultrasound, strategic use of CT, MRI/MRCP, endoscopic ultrasound, and ERCP based on clinical suspicion and initial findings.

3. Liver biopsy indications: When to pursue histologic diagnosis for unclear etiology, suspected infiltrative disease, or grading/staging of chronic liver disease.

4. Elastography: FibroScan and MR elastography for non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis.

5. Genetic testing: Appropriate use of genetic panels for hereditary cholestatic syndromes and metabolic liver diseases.

Evidence-Based Management

1. Alcoholic hepatitis: Maddrey's discriminant function, MELD, and Lille scores to guide corticosteroid therapy; pentoxifylline as alternative.

2. Primary biliary cholangitis: UDCA dosing (13-15 mg/kg/day), monitoring response biochemically at 12 months, and adding second-line therapies (obeticholic acid, bezafibrate) for incomplete response.

3. Autoimmune hepatitis: Induction with prednisone ± azathioprine, followed by maintenance; monitoring treatment response and managing relapse.

4. Drug-induced liver injury: Causality assessment using RUCAM score; N-acetylcysteine protocol for acetaminophen toxicity.

5. Viral hepatitis: Current antiviral regimens for hepatitis B, C, D, and E; monitoring for complications of chronic infection.

Management of Complications

1. Portal hypertension: Primary and secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding; management of ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

2. Hepatic encephalopathy: Grading, precipitants, and management with lactulose, rifaximin; prevention of recurrence.

3. Hepatorenal syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, prevention strategies, and management with vasoconstrictors and albumin.

4. Pruritus management: Stepwise approach using cholestyramine, rifampin, naltrexone, and sertraline.

5. Nutritional management: BCAA supplementation in encephalopathy; medium-chain triglyceride supplementation in cholestasis; vitamin K in coagulopathy.

Specialized Therapeutic Interventions

1. Biliary interventions: ERCP with sphincterotomy, stone extraction, stent placement; percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; EUS-guided biliary drainage.

2. Transplant evaluation: Indications, contraindications, and timing for referral based on MELD score; special considerations for alcoholic liver disease, HCC, and cholestatic disorders.

3. Palliative approaches: Management of malignant biliary obstruction with consideration of prognosis, performance status, and quality of life.

4. Novel therapies: FXR agonists for NASH and cholestatic disorders; immune checkpoint inhibitors for HCC; antifibrotics in development.

5. Management of special scenarios: Acute-on-chronic liver failure, pregnancy-related liver disease, and post-transplant complications.

Quality and Systems-Based Practice

1. Preventive care: Vaccination against hepatitis A/B; screening high-risk populations for viral hepatitis; surveillance for HCC in cirrhosis.

2. Quality metrics: Evidence-based quality indicators for management of cirrhosis, including timeliness of paracentesis, appropriate prophylaxis, and vaccination.

3. Transition of care: Coordination between inpatient and outpatient care for patients with chronic liver disease; preventing readmission.

4. Resource utilization: Cost-effective approaches to diagnosis and management of jaundice and liver disease.

5. Multidisciplinary management: Coordination between hepatology, interventional radiology, oncology, surgery, and transplant services for optimal outcomes.