ABIM - Heart Murmurs

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for ABIM from the Hypertension Overview tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

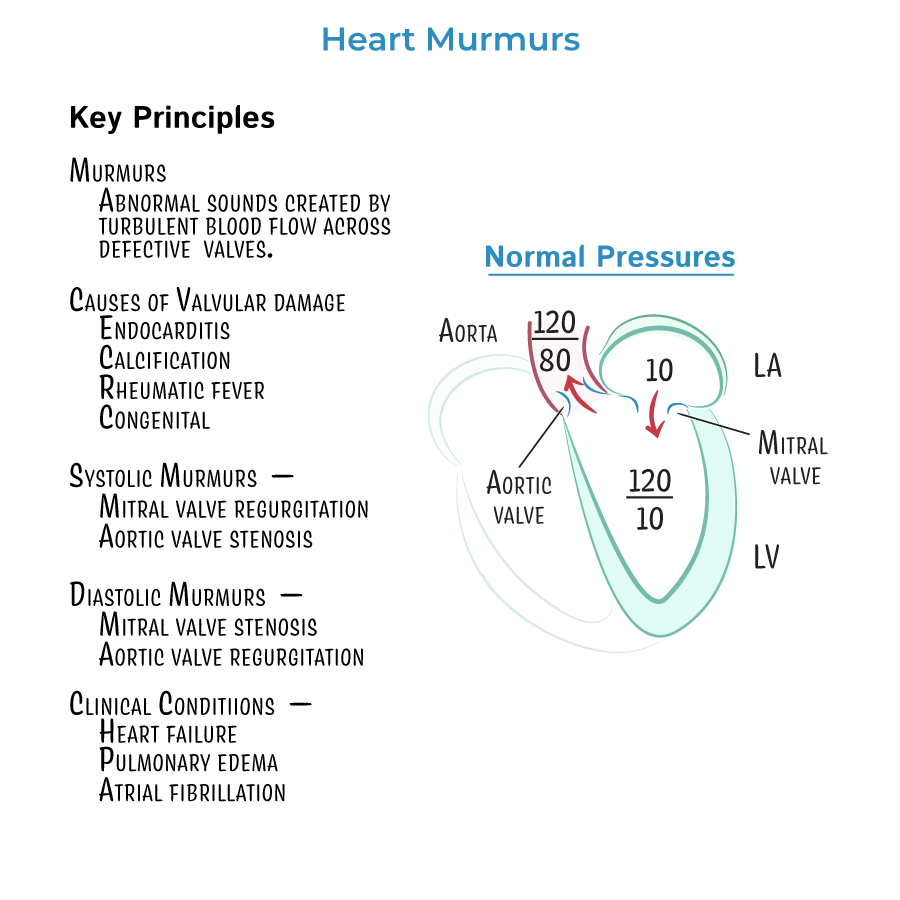

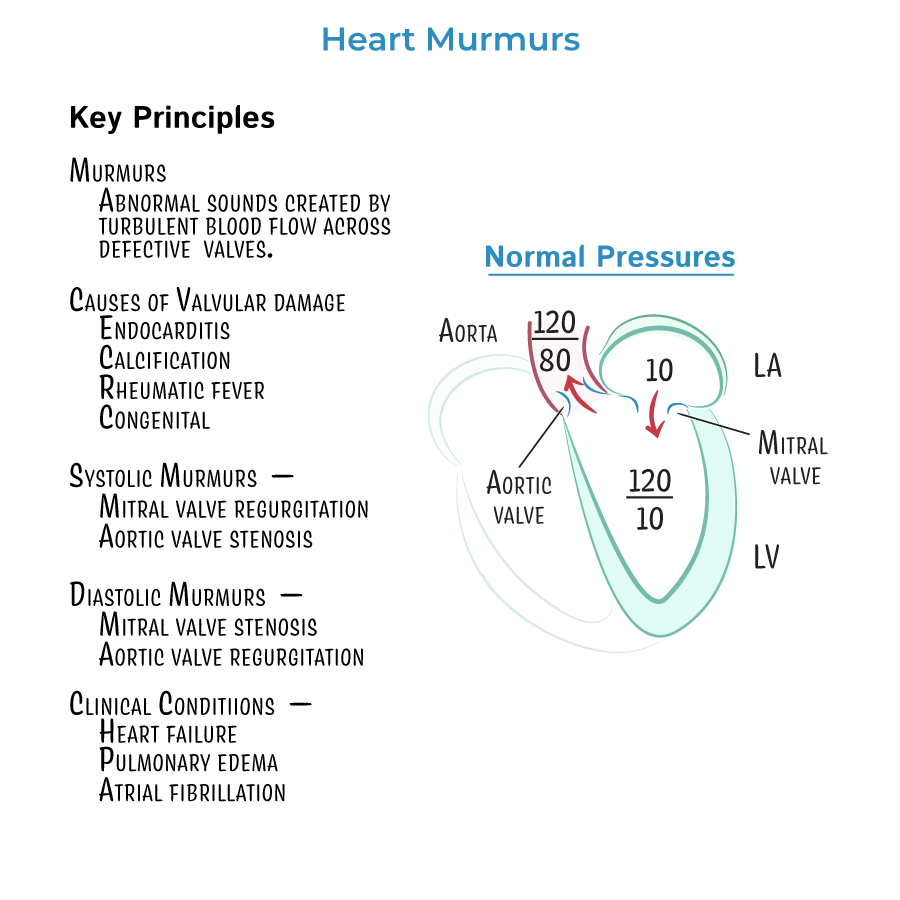

1. Heart murmurs are generated by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves and may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (backflow) of blood through incompletely closed valves.

2. Aortic stenosis produces a crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the right upper sternal border. The murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and is associated with exertional syncope, angina, and heart failure. Diagnosis is confirmed with transthoracic echocardiography. Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is an indication for valve replacement.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a blowing holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It can result from mitral valve prolapse, papillary muscle dysfunction, endocarditis, or left ventricular dilation. In chronic MR, symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, and atrial fibrillation. Echocardiography evaluates severity and left ventricular size and function. Surgical repair or replacement is indicated for symptomatic patients or those with reduced ejection fraction (less than 60%) or left ventricular dilation.

4. Aortic regurgitation is characterized by an early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border, often with the patient leaning forward and exhaling. Clinical signs include wide pulse pressure, bounding pulses, and head bobbing (Corrigan's sign). Causes include aortic root dilation, congenital valve abnormalities, and infective endocarditis. Chronic aortic regurgitation may require surgery if symptoms develop or left ventricular systolic function declines (EF below 55%).

5. Mitral stenosis presents with a low-pitched diastolic rumble heard at the apex and preceded by an opening snap. The murmur is enhanced in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Left atrial enlargement can lead to atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension. Intervention is considered for symptomatic patients with severe stenosis or evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Percutaneous balloon valvotomy is the preferred initial procedure in appropriate candidates.

6. Mitral valve prolapse produces a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur best heard at the apex. The murmur becomes louder with Valsalva and standing due to decreased preload. It is more common in women and may be associated with connective tissue disorders. Most cases are benign but may progress to significant mitral regurgitation.

7. Evaluation of a new murmur begins with a focused history and physical exam. Key findings such as radiation, changes with position, and murmur timing guide clinical suspicion. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic tool to assess valve anatomy and function.

8. Maneuvers can help differentiate murmurs. Squatting increases preload and afterload, which intensifies most murmurs except mitral valve prolapse and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Valsalva decreases preload, making MVP and HOCM murmurs louder and most others softer. Handgrip increases afterload, enhancing regurgitant murmurs and decreasing murmurs of aortic stenosis and HOCM.

9. Murmurs from tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic valve disease are typically best heard along the left lower sternal border and may increase with inspiration. Carvallo’s sign helps distinguish tricuspid regurgitation from mitral regurgitation.

10. Infective endocarditis should be considered when a new murmur is detected in a febrile patient, particularly with risk factors such as intravenous drug use or recent dental procedures. Diagnosis includes blood cultures and echocardiography, with transesophageal echocardiography providing higher sensitivity.

1. Rheumatic heart disease is the most common cause of mitral stenosis worldwide and is associated with progressive fibrotic narrowing of the mitral valve orifice.

2. In mitral stenosis, the elevated left atrial pressure can lead to pulmonary edema, atrial fibrillation, and systemic embolization.

3. Chronic mitral and aortic regurgitation cause volume overload of the left ventricle, resulting in eccentric hypertrophy. This leads to progressive ventricular dilation and eventual systolic dysfunction if untreated.

4. Chronic pressure overload from aortic stenosis leads to concentric hypertrophy. Patients remain asymptomatic for years until decompensation occurs with angina, syncope, or heart failure.

5. In patients with atrial fibrillation due to mitral stenosis, anticoagulation is typically recommended even if the CHA₂DS₂-VASc score is low, due to high thromboembolic risk associated with left atrial enlargement.

6. Prosthetic valves require lifelong surveillance. Mechanical valves require anticoagulation, typically with warfarin, targeting an INR based on valve location and type.

7. Patent ductus arteriosus produces a continuous murmur that peaks at S2 and is best heard below the left clavicle. It is more commonly encountered in pediatric patients and congenital heart disease clinics but may occasionally be seen in adults.

8. Murmurs that change with body position or respiration should be carefully documented and may help localize the lesion. For example, murmurs of right-sided valves (e.g., tricuspid regurgitation) typically increase with inspiration due to increased venous return.

9. Diastolic murmurs are nearly always pathologic and should prompt echocardiographic evaluation, even in asymptomatic patients.

10. Serial echocardiograms are recommended for patients with known valvular disease to monitor progression and guide timing for surgical referral.

1. Heart murmurs are generated by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves and may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (backflow) of blood through incompletely closed valves.

2. Aortic stenosis produces a crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the right upper sternal border. The murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and is associated with exertional syncope, angina, and heart failure. Diagnosis is confirmed with transthoracic echocardiography. Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is an indication for valve replacement.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a blowing holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It can result from mitral valve prolapse, papillary muscle dysfunction, endocarditis, or left ventricular dilation. In chronic MR, symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, and atrial fibrillation. Echocardiography evaluates severity and left ventricular size and function. Surgical repair or replacement is indicated for symptomatic patients or those with reduced ejection fraction (less than 60%) or left ventricular dilation.

4. Aortic regurgitation is characterized by an early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border, often with the patient leaning forward and exhaling. Clinical signs include wide pulse pressure, bounding pulses, and head bobbing (Corrigan's sign). Causes include aortic root dilation, congenital valve abnormalities, and infective endocarditis. Chronic aortic regurgitation may require surgery if symptoms develop or left ventricular systolic function declines (EF below 55%).

5. Mitral stenosis presents with a low-pitched diastolic rumble heard at the apex and preceded by an opening snap. The murmur is enhanced in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Left atrial enlargement can lead to atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension. Intervention is considered for symptomatic patients with severe stenosis or evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Percutaneous balloon valvotomy is the preferred initial procedure in appropriate candidates.

6. Mitral valve prolapse produces a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur best heard at the apex. The murmur becomes louder with Valsalva and standing due to decreased preload. It is more common in women and may be associated with connective tissue disorders. Most cases are benign but may progress to significant mitral regurgitation.

7. Evaluation of a new murmur begins with a focused history and physical exam. Key findings such as radiation, changes with position, and murmur timing guide clinical suspicion. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic tool to assess valve anatomy and function.

8. Maneuvers can help differentiate murmurs. Squatting increases preload and afterload, which intensifies most murmurs except mitral valve prolapse and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Valsalva decreases preload, making MVP and HOCM murmurs louder and most others softer. Handgrip increases afterload, enhancing regurgitant murmurs and decreasing murmurs of aortic stenosis and HOCM.

9. Murmurs from tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic valve disease are typically best heard along the left lower sternal border and may increase with inspiration. Carvallo’s sign helps distinguish tricuspid regurgitation from mitral regurgitation.

10. Infective endocarditis should be considered when a new murmur is detected in a febrile patient, particularly with risk factors such as intravenous drug use or recent dental procedures. Diagnosis includes blood cultures and echocardiography, with transesophageal echocardiography providing higher sensitivity.

1. Rheumatic heart disease is the most common cause of mitral stenosis worldwide and is associated with progressive fibrotic narrowing of the mitral valve orifice.

2. In mitral stenosis, the elevated left atrial pressure can lead to pulmonary edema, atrial fibrillation, and systemic embolization.

3. Chronic mitral and aortic regurgitation cause volume overload of the left ventricle, resulting in eccentric hypertrophy. This leads to progressive ventricular dilation and eventual systolic dysfunction if untreated.

4. Chronic pressure overload from aortic stenosis leads to concentric hypertrophy. Patients remain asymptomatic for years until decompensation occurs with angina, syncope, or heart failure.

5. In patients with atrial fibrillation due to mitral stenosis, anticoagulation is typically recommended even if the CHA₂DS₂-VASc score is low, due to high thromboembolic risk associated with left atrial enlargement.

6. Prosthetic valves require lifelong surveillance. Mechanical valves require anticoagulation, typically with warfarin, targeting an INR based on valve location and type.

7. Patent ductus arteriosus produces a continuous murmur that peaks at S2 and is best heard below the left clavicle. It is more commonly encountered in pediatric patients and congenital heart disease clinics but may occasionally be seen in adults.

8. Murmurs that change with body position or respiration should be carefully documented and may help localize the lesion. For example, murmurs of right-sided valves (e.g., tricuspid regurgitation) typically increase with inspiration due to increased venous return.

9. Diastolic murmurs are nearly always pathologic and should prompt echocardiographic evaluation, even in asymptomatic patients.

10. Serial echocardiograms are recommended for patients with known valvular disease to monitor progression and guide timing for surgical referral.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

1. Heart murmurs are generated by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves and may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (backflow) of blood through incompletely closed valves.

2. Aortic stenosis produces a crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the right upper sternal border. The murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and is associated with exertional syncope, angina, and heart failure. Diagnosis is confirmed with transthoracic echocardiography. Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is an indication for valve replacement.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a blowing holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It can result from mitral valve prolapse, papillary muscle dysfunction, endocarditis, or left ventricular dilation. In chronic MR, symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, and atrial fibrillation. Echocardiography evaluates severity and left ventricular size and function. Surgical repair or replacement is indicated for symptomatic patients or those with reduced ejection fraction (less than 60%) or left ventricular dilation.

4. Aortic regurgitation is characterized by an early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border, often with the patient leaning forward and exhaling. Clinical signs include wide pulse pressure, bounding pulses, and head bobbing (Corrigan's sign). Causes include aortic root dilation, congenital valve abnormalities, and infective endocarditis. Chronic aortic regurgitation may require surgery if symptoms develop or left ventricular systolic function declines (EF below 55%).

5. Mitral stenosis presents with a low-pitched diastolic rumble heard at the apex and preceded by an opening snap. The murmur is enhanced in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Left atrial enlargement can lead to atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension. Intervention is considered for symptomatic patients with severe stenosis or evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Percutaneous balloon valvotomy is the preferred initial procedure in appropriate candidates.

6. Mitral valve prolapse produces a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur best heard at the apex. The murmur becomes louder with Valsalva and standing due to decreased preload. It is more common in women and may be associated with connective tissue disorders. Most cases are benign but may progress to significant mitral regurgitation.

7. Evaluation of a new murmur begins with a focused history and physical exam. Key findings such as radiation, changes with position, and murmur timing guide clinical suspicion. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic tool to assess valve anatomy and function.

8. Maneuvers can help differentiate murmurs. Squatting increases preload and afterload, which intensifies most murmurs except mitral valve prolapse and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Valsalva decreases preload, making MVP and HOCM murmurs louder and most others softer. Handgrip increases afterload, enhancing regurgitant murmurs and decreasing murmurs of aortic stenosis and HOCM.

9. Murmurs from tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic valve disease are typically best heard along the left lower sternal border and may increase with inspiration. Carvallo’s sign helps distinguish tricuspid regurgitation from mitral regurgitation.

10. Infective endocarditis should be considered when a new murmur is detected in a febrile patient, particularly with risk factors such as intravenous drug use or recent dental procedures. Diagnosis includes blood cultures and echocardiography, with transesophageal echocardiography providing higher sensitivity.

1. Heart murmurs are generated by turbulent blood flow across abnormal cardiac valves and may be due to stenosis (narrowing) or regurgitation (backflow) of blood through incompletely closed valves.

2. Aortic stenosis produces a crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the right upper sternal border. The murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and is associated with exertional syncope, angina, and heart failure. Diagnosis is confirmed with transthoracic echocardiography. Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is an indication for valve replacement.

3. Mitral regurgitation causes a blowing holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex and radiating to the axilla. It can result from mitral valve prolapse, papillary muscle dysfunction, endocarditis, or left ventricular dilation. In chronic MR, symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, and atrial fibrillation. Echocardiography evaluates severity and left ventricular size and function. Surgical repair or replacement is indicated for symptomatic patients or those with reduced ejection fraction (less than 60%) or left ventricular dilation.

4. Aortic regurgitation is characterized by an early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border, often with the patient leaning forward and exhaling. Clinical signs include wide pulse pressure, bounding pulses, and head bobbing (Corrigan's sign). Causes include aortic root dilation, congenital valve abnormalities, and infective endocarditis. Chronic aortic regurgitation may require surgery if symptoms develop or left ventricular systolic function declines (EF below 55%).

5. Mitral stenosis presents with a low-pitched diastolic rumble heard at the apex and preceded by an opening snap. The murmur is enhanced in the left lateral decubitus position. It is most commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease. Left atrial enlargement can lead to atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension. Intervention is considered for symptomatic patients with severe stenosis or evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Percutaneous balloon valvotomy is the preferred initial procedure in appropriate candidates.

6. Mitral valve prolapse produces a mid-systolic click followed by a late systolic murmur best heard at the apex. The murmur becomes louder with Valsalva and standing due to decreased preload. It is more common in women and may be associated with connective tissue disorders. Most cases are benign but may progress to significant mitral regurgitation.

7. Evaluation of a new murmur begins with a focused history and physical exam. Key findings such as radiation, changes with position, and murmur timing guide clinical suspicion. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic tool to assess valve anatomy and function.

8. Maneuvers can help differentiate murmurs. Squatting increases preload and afterload, which intensifies most murmurs except mitral valve prolapse and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Valsalva decreases preload, making MVP and HOCM murmurs louder and most others softer. Handgrip increases afterload, enhancing regurgitant murmurs and decreasing murmurs of aortic stenosis and HOCM.

9. Murmurs from tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic valve disease are typically best heard along the left lower sternal border and may increase with inspiration. Carvallo’s sign helps distinguish tricuspid regurgitation from mitral regurgitation.

10. Infective endocarditis should be considered when a new murmur is detected in a febrile patient, particularly with risk factors such as intravenous drug use or recent dental procedures. Diagnosis includes blood cultures and echocardiography, with transesophageal echocardiography providing higher sensitivity.

- --

HIGH YIELD