ABIM - H. pylori Infection

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for ABIM from the Helicobacter pylori tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for ABIM.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for ABIM.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

Helicobacter pylori - Pathogen Characteristics

1. H. pylori is a spiral, Gram-negative rod that can appear coccoid in older cultures.

2. It is catalase, oxidase, and urease positive - key characteristics for diagnostic testing.

3. Microaerobic organism requiring reduced oxygen and increased carbon dioxide for growth.

4. Human-to-human transmission with infection typically occurring during childhood.

5. Creates life-long colonization with symptoms often manifesting during adulthood.

Pathophysiology and Virulence Factors

1. Urease converts urea to ammonia and bicarbonate to neutralize gastric acids.

2. Multiple flagella provide corkscrew motility through gastric mucus.

3. Vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) promotes pore formation and induces apoptosis and necrosis.

4. Cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) product promotes proliferation and morphological changes.

5. Type IV secretion systems inject CagA effector protein into host cells.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

1. Gastritis presents with neutrophilic and mononuclear cell infiltration of stomach lining.

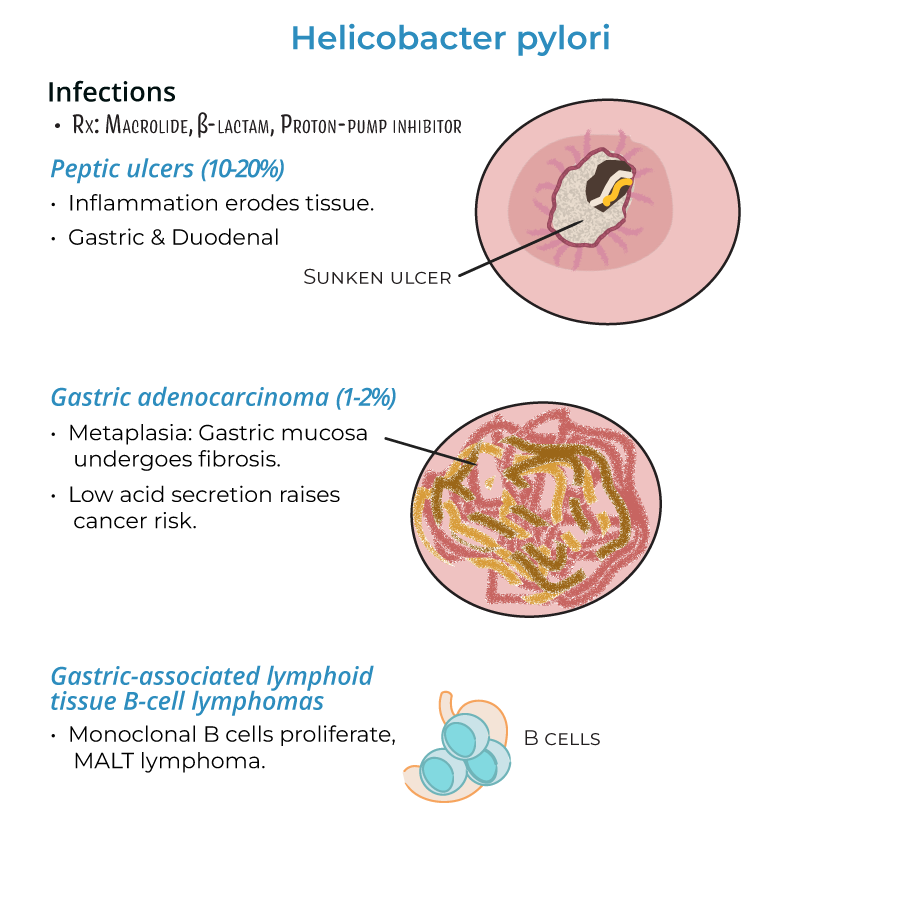

2. Peptic ulcers develop in 10-20% of gastritis patients, affecting stomach or duodenum.

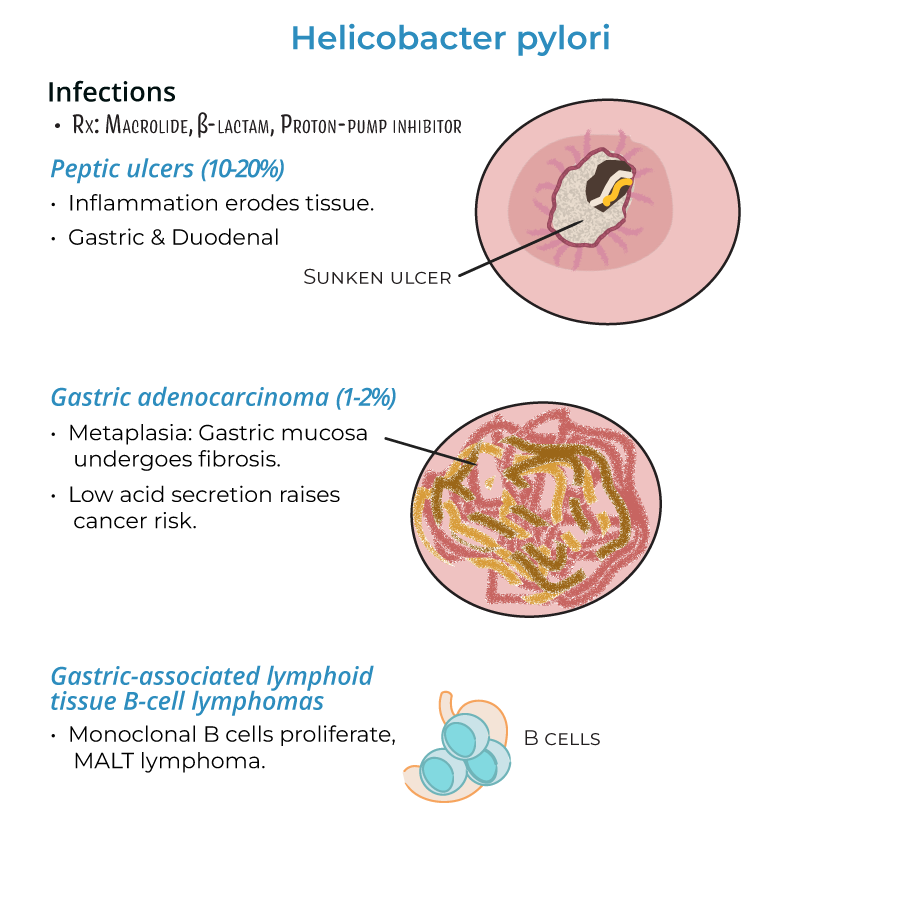

3. Gastric adenocarcinoma occurs in approximately 1-2% of chronic infections.

4. MALT B-cell lymphomas form when monoclonal B cells proliferate in gastric lymphoid tissue.

5. Inflammation can be localized (antral) or widespread (pangastritis), predicting different complications.

Treatment Approach

1. Standard therapy includes macrolides, beta-lactams, and proton-pump inhibitors.

2. Treatment is essential due to potential for severe consequences from chronic infection.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Advanced Pathophysiology

1. Infection triggers host production of IL-8, a pro-inflammatory cytokine recruiting neutrophils.

2. Neutrophils release harmful molecules causing damage to host tissues.

3. Bacteria protect themselves by producing superoxide dismutase and catalase to detoxify reactive oxygen species.

4. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxin has lower toxicity compared to other Gram-negative bacteria.

5. T-helper 1 cells are implicated in the inflammatory response to H. pylori.

Clinical Patterns and Risk Stratification

1. Antral gastritis associates with increased acid production and duodenal ulcers.

2. Pangastritis (multifocal inflammation) associates with atrophy, reduced acid production, and gastric cancer risk.

3. H. pylori destroys mucosa, allowing acids and toxins access to deeper tissues.

4. Chronic inflammation leads to metaplasia where gastric mucosa is replaced by fibrotic tissue.

5. Reduced gastric acid secretion correlates with higher risk of adenocarcinoma.

6. Severe ulceration can lead to bleeding, perforation, and metaplasia.

Non-Gastric Helicobacter Infections

1. Enterohepatic helicobacters (H. cinaedi and H. fennelliae) can cause gastroenteritis and bacteremia.

2. These species primarily affect immunocompromised individuals.

3. Unlike H. pylori, these species invade the intestines and liver rather than the stomach.

Diagnostic Considerations

1. Inflammation can be localized to one area or widespread.

2. Some individuals remain asymptomatic, while others experience acute symptoms of nausea, bloating, and vomiting.

3. In MALT lymphomas, lymphoid tissues infiltrate the stomach in response to H. pylori infection.

4. Progression from gastritis to more serious conditions occurs in a subset of patients.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Advanced Diagnosis and Testing

1. Test selection should consider clinical context, medication use, and cost-effectiveness.

2. Non-invasive testing: urea breath test (most accurate non-invasive test), stool antigen test (cost-effective), serology (limited by inability to confirm active infection).

3. Invasive testing: endoscopy with biopsy for histology, rapid urease test, and culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

4. Testing for antimicrobial resistance increasingly important due to rising clarithromycin resistance rates.

5. Post-treatment testing to confirm eradication recommended at least 4 weeks after therapy and after PPI discontinuation.

Contemporary Treatment Guidelines

1. Empiric therapy selection should account for local resistance patterns and previous antibiotic exposure.

2. First-line options: clarithromycin triple therapy, bismuth quadruple therapy, concomitant therapy, sequential therapy.

3. Salvage therapy: levofloxacin-based regimens, rifabutin-based regimens, high-dose dual therapy.

4. Treatment duration: 14 days generally preferred over shorter courses.

5. Bismuth-based regimens particularly important in areas with high clarithromycin resistance.

6. Antibiotic stewardship considerations given rising resistance patterns.

Special Clinical Scenarios

1. Management approach for refractory H. pylori infection.

2. Considerations for patients requiring chronic NSAID or aspirin therapy.

3. Approach to incidental H. pylori discovered during endoscopy for other indications.

4. Management of H. pylori in patients with functional dyspepsia.

5. Testing and management in patients with a family history of gastric cancer.

6. Relationship between H. pylori and unexplained iron deficiency anemia or ITP.

Long-term Management

1. Surveillance strategies for patients with pre-neoplastic lesions.

2. Follow-up protocols after successful H. pylori eradication.

3. Management of persistent symptoms despite successful eradication.

4. Risk stratification for gastric cancer development post-eradication.

5. Cost-effectiveness of population-based screening and treatment strategies.

6. Impact of H. pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer.