ABIM - Gastritis & Peptic Ulcer Disease

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for ABIM from the Gastritis & Peptic Ulcer Disease tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for ABIM.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for ABIM.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

Disease Definitions & Pathophysiology

1. Gastritis is inflammation of the gastric mucosa; it can be diffuse or multi-focal.

2. Peptic ulcer disease is characterized by ulcers in the stomach and/or duodenum that penetrate the mucosa to reach the deeper layers of the GI tract.

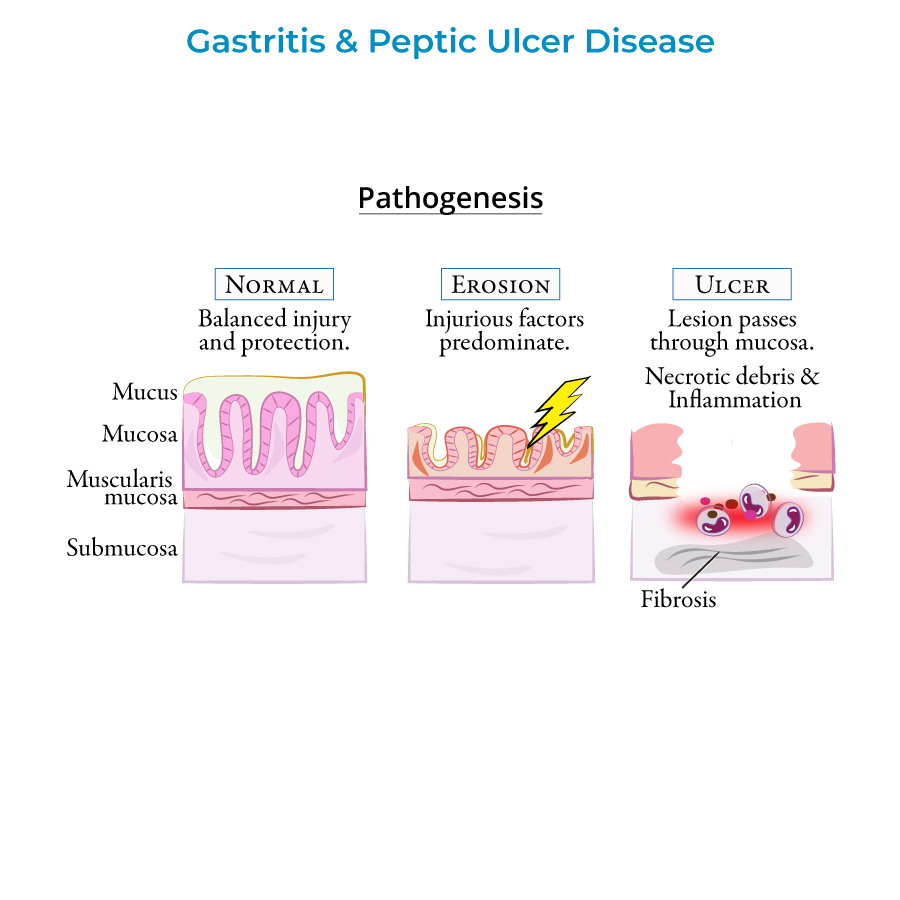

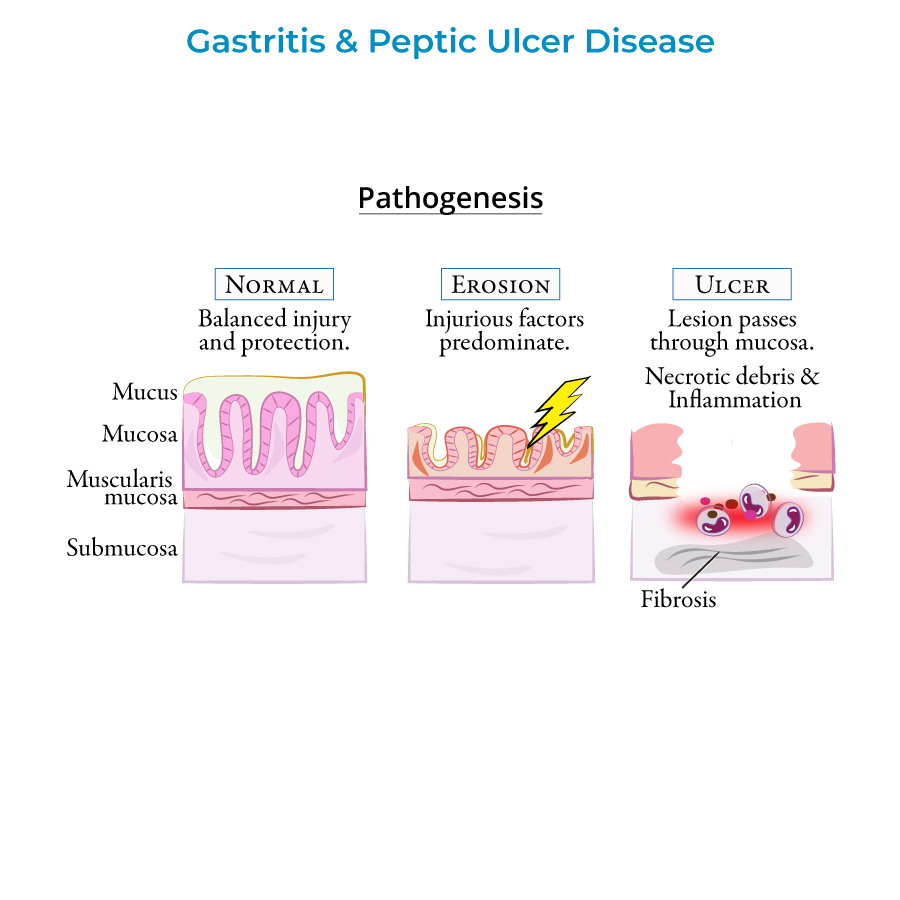

3. In healthy tissue, damaging and protective factors of the GI tract are in balance; as injurious factors predominate, inflammation and erosions form.

4. Ulcers develop when lesions erode through the mucosa and deeper layers, showing necrotic debris with leukocyte infiltration and fibrosis in chronic cases.

5. Chronic inflammation from either disorder can pave the way for malignancy, necessitating vigilant monitoring.

Clinical Manifestations & Differential Diagnosis

1. Signs and symptoms include epigastric pain, GI bleeding, nausea or vomiting; many patients are asymptomatic, especially in early phases.

2. Gastric ulcer pain increases upon eating, leading patients to avoid food and lose weight.

3. Duodenal ulcer pain relieves with eating and may be associated with weight gain, though these patterns are not always consistent.

4. Perforation presents with sudden abdominal pain, tachycardia, and abdominal rigidity.

5. Gastric outlet obstruction manifests with early satiety, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and pain.

Diagnostic Approach

1. Upper endoscopy is used to visualize lesions and obtain biopsies to assess inflammation, H. pylori infection, and malignancy.

2. Urea breath test and stool antigen tests are non-invasive methods for detecting active H. pylori infection.

3. H. pylori antibody serologies do not distinguish between active and inactive disease.

4. For patients younger than 60 years without alarming symptoms, focus on non-invasive H. pylori testing and PPI response.

5. For patients older than 60 years or with alarming symptoms (weight loss, anemia, bloody stools, dysphagia), upper endoscopy should be performed.

Treatment & Management

1. Treatment involves proton pump inhibitors, NSAID discontinuation, and H. pylori eradication with antibiotics when present.

2. Follow-up testing is necessary to confirm H. pylori eradication and prevent relapse.

3. Non-ulcer dyspepsia is treated with proton pump inhibitors after ruling out cancer in those over 55 years old.

4. Hemorrhage complications can be treated with endoscopic hemostasis therapies and proton pump inhibitors.

5. For gastric outlet obstruction, try treatment of the underlying peptic ulcer disease before attempting surgical solutions.

Complications & Emergency Management

1. Peptic ulcers are the most common cause of upper GI bleeding.

2. Perforation occurs when an ulcer creates a hole in the GI tract; this is an emergency that can cause peritonitis.

3. Perforation has a high mortality rate (up to 30%) and presents with pneumoperitoneum (free air under diaphragm) on imaging.

4. "Penetration" occurs when a peptic ulcer erodes into another organ instead of opening into the peritoneum.

5. Gastric outlet obstruction is due to inflammation and edema in acute cases; fibrosis and scarring in chronic cases.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Etiology & Risk Factors

1. H. pylori infection and NSAID use are top causes of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.

2. H. pylori is present in approximately 70% of gastric ulcer cases and 90% of duodenal ulcer cases.

3. NSAIDs block prostaglandin synthesis necessary for mucous production, while alcohol causes direct damage to the mucosal lining.

4. Cigarette smoking is an important risk factor, while psychological stress and spicy foods do not cause peptic ulcers.

5. H. pylori is classified as a class I carcinogen because it causes chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

Types & Special Presentations

1. Acute gastritis occurs with sudden insult to the gastric mucosa, commonly from NSAIDs, aspirin, and alcohol.

2. Chronic gastritis often leads to atrophy with loss of gastric glands and folds, increasing malignancy risk.

3. Stress ulcers include Curling ulcers (systemic burns, hypovolemia) and Cushing ulcers (brain injury, increased vagal stimulation).

4. Autoimmune gastritis involves T-cell mediated destruction of parietal cells and can lead to pernicious anemia.

5. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare cause of gastric ulcers that should be considered in refractory cases.

Evidence-Based Management

1. Gastric ulcers have a higher risk of malignancy (5-10%) compared to duodenal ulcers, making early detection crucial.

2. H. pylori eradication significantly reduces risk of ulcer recurrence and should be confirmed with follow-up testing.

3. Peptic ulcers caused by H. pylori are declining due to improved sanitation, while NSAID-related cases are increasing.

4. Hemorrhagic bleeding can be deadly, requiring prompt treatment with proton pump inhibitors and endoscopic intervention.

5. Urea breath test and stool antigen tests are preferred over antibody serology for detecting active H. pylori infection.

Special Populations

1. H. pylori is present in nearly half the world's population, but not everyone infected develops gastritis or cancer.

2. Patients with autoimmune gastritis are likely to have other autoimmune disorders.

3. Autoimmune gastritis can be concomitant with H. pylori infection, requiring checking for and treating H. pylori even when autoimmune etiology is indicated.

4. Cases of NSAID-related peptic ulcers are increasing, possibly due to an aging population relying on NSAIDs for pain relief.

5. For patients with alarming symptoms (weight loss, anemia, bloody stools, dysphagia), upper endoscopy should be prioritized regardless of age.

Long-Term Considerations

1. Chronic gastritis from H. pylori increases the risk of peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, and primary gastric MALT lymphomas.

2. Early detection and treatment of gastric ulcers is crucial because of their higher malignancy risk.

3. Atrophic gastritis is characterized by loss of gastric glands and folds with pale mucosa and increased vascular visibility.

4. Gastric outlet obstruction due to chronic fibrosis and scarring may require surgical intervention if medical therapy fails.

5. Penetration of ulcers into adjacent organs requires different management approaches than free perforation into the peritoneum.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Advanced Clinical Management

1. First-line H. pylori treatment: 14-day triple therapy (PPI + clarithromycin + amoxicillin/metronidazole) or 10-14 day quadruple therapy (PPI + bismuth + tetracycline + metronidazole).

2. Second-line therapies for treatment failures: Levofloxacin-based triple therapy, rifabutin-based triple therapy, or high-dose dual therapy (PPI + amoxicillin).

3. Risk assessment for recurrent bleeding: Forrest classification of ulcers (Ia-III) guides need for endoscopic intervention and determines rebleeding risk.

4. PPI prophylaxis: Indicated for high-risk NSAID users (age >65, prior PUD history, concurrent anticoagulants or steroids, high-dose or multiple NSAIDs).

5. Management of antiplatelet/anticoagulant-associated bleeding: Stratify cardiovascular vs. bleeding risk; consider early resumption of aspirin (within 3-7 days) after high-risk cardiovascular events.

Emerging Concepts & Updates

1. H. pylori resistance patterns: Increasing clarithromycin resistance (>15% in many regions) impacts first-line therapy selection and success rates.

2. Vonoprazan, a potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB), shows superior acid suppression and improved H. pylori eradication rates compared to PPIs.

3. Post-eradication dyspepsia: Up to 30% of patients have persistent symptoms after successful H. pylori eradication, requiring alternative management strategies.

4. Microbiome considerations: H. pylori eradication may influence gut microbiome composition with potential metabolic consequences.

5. Cancer surveillance recommendations: Patients with intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, or family history of gastric cancer require tailored endoscopic surveillance protocols.