ABIM - Cortisol Physiology & Pathology

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for ABIM from the Cortisol Physiology & Pathology tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end of this document that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards. See the tutorial notes for further details and relevant links.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

Pathophysiology and Classification

1. Regulation pathway: Cortisol is the primary glucocorticoid secreted by the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex, with secretion triggered by ACTH from the anterior pituitary in response to CRH from the hypothalamus.

2. Negative feedback: Cortisol has a negative feedback effect at both the hypothalamus and pituitary, where it blocks the release of CRH and ACTH, respectively.

3. Classification system: Hypercortisolism (Cushing's Syndrome) is classified as either ACTH-dependent (elevated cortisol caused by elevated ACTH) or ACTH-independent (elevated cortisol not caused by elevated ACTH).

4. Etiology breakdown: ACTH-independent cases are most commonly due to exogenous glucocorticoids (iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome), while endogenous cases are most often ACTH-dependent, with Cushing's Disease (pituitary adenoma) being the most common form.

5. Physiologic mimics: Important to rule out physiologic causes and certain medical conditions that raise cortisol: pregnancy, alcoholism, anorexia, obesity, depression, and uncontrolled diabetes.

Clinical Evaluation

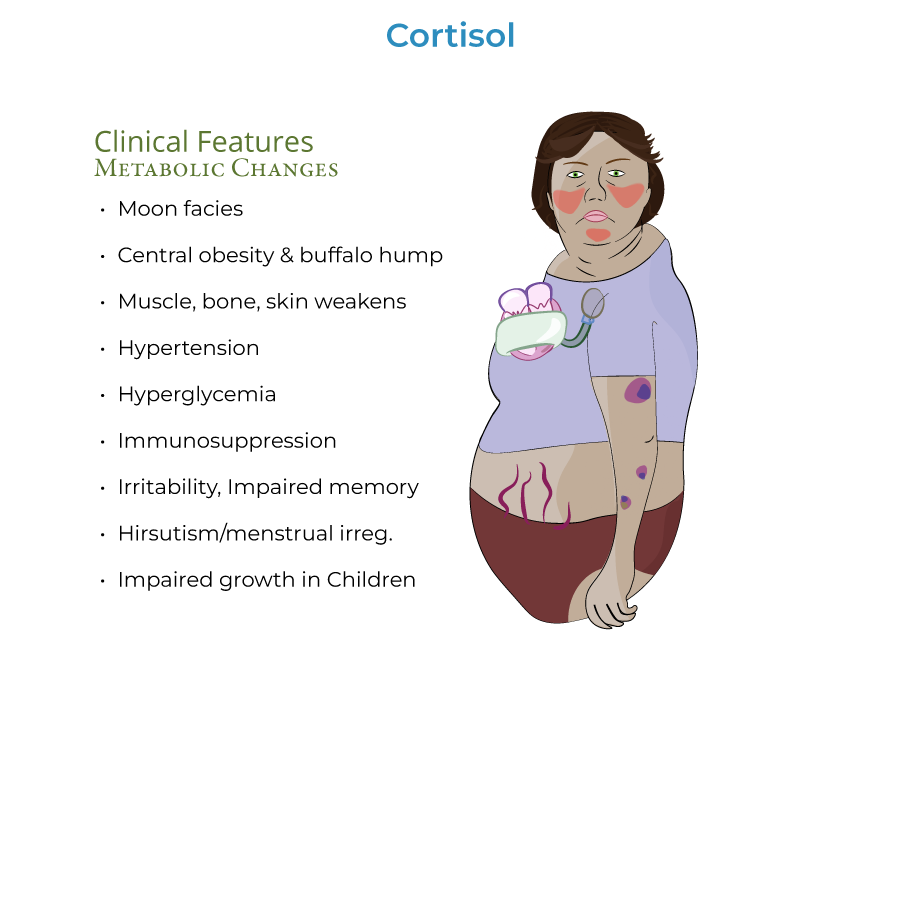

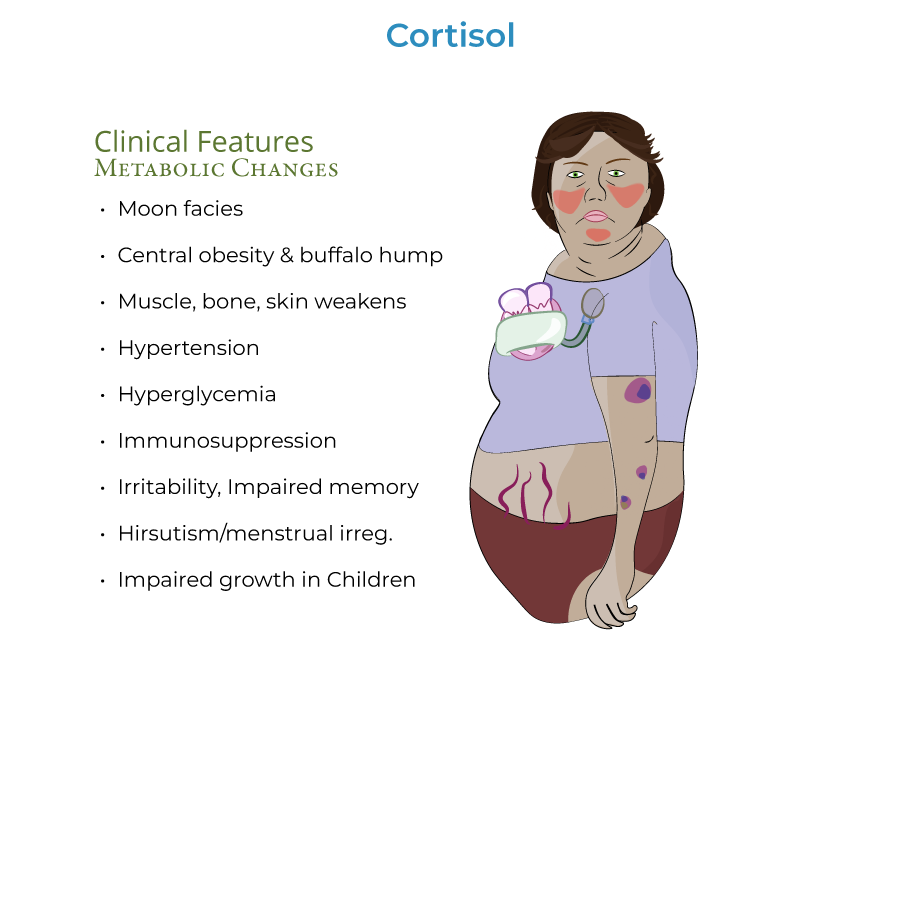

1. Classic findings: "Moon facies" (rounded face/neck due to fat accumulation), central/truncal obesity with "buffalo hump," and red/purple striae on abdomen, breasts, thighs, and buttocks.

2. Metabolic manifestations: Hyperglycemia may progress to diabetes mellitus due to increased gluconeogenesis and insulin resistance; hypertension develops via increased cardiac contractility and extracellular fluid volume.

3. Body composition: Muscle atrophy particularly apparent in extremities, making limbs appear disproportionately thin, with increased fracture risk due to osteoporosis.

4. Screening approach: 24-hour urine samples, midnight salivary samples, or dexamethasone suppression test are appropriate initial screening tests.

5. Diagnostic algorithm: After confirming hypercortisolism (elevated cortisol and/or lack of suppression with dexamethasone), measure plasma ACTH to determine etiology.

Etiology Workup

1. ACTH-independent causes: With low/suppressed ACTH, consider adrenal tumor (adenoma more common than carcinoma) or exogenous glucocorticoids.

2. ACTH-dependent causes: With elevated/not suppressed ACTH, consider pituitary adenoma (Cushing's Disease) or ectopic ACTH production.

3. Localization techniques: Inferior petrosal sampling helps determine source of excess ACTH - central ACTH higher than peripheral levels suggests pituitary tumor, while central ACTH less than or equal to peripheral levels suggests ectopic tumor.

4. Ectopic sources: Small cell lung cancer and bronchial tumors are common sources of ectopic ACTH production.

5. Adrenal imaging: Expect a unilateral tumor with contralateral adrenal atrophy in adrenal causes due to lack of ACTH stimulation.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Cortisol Physiology and Effects

1. Circadian pattern: Cortisol secretion is pulsatile and circadian; levels are highest upon waking and decline to reach their lowest levels around bedtime – requires consideration of sleep schedule when assessing.

2. Plasma binding: Approximately 85% of cortisol in blood is bound to plasma proteins, giving it a long half-life, while urine free cortisol and salivary cortisol measurements reflect unbound cortisol.

3. Immunologic effects: Suppression of inflammatory and immune responses occurs via inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediators such as monocytes, neutrophils, and cytokines, increasing vulnerability to tuberculosis and fungal infections.

4. Metabolic effects: Increases carbohydrate metabolism (increases gluconeogenesis, decreases insulin sensitivity), protein metabolism (decreases protein stores except in liver), and fat metabolism (increases lipolysis but paradoxically associated with obesity).

5. Bone effects: Increases bone resorption and reduces formation of new bone tissue, resulting in osteoporosis and increased fracture risk.

Clinical Subtleties

1. Endocrine disruption: Secretion of thyrotropin, gonadotropin, and growth hormone are suppressed in Cushing's Disease, affecting multiple hormonal systems.

2. Psychiatric manifestations: Patients may experience emotional or psychiatric disturbances, such as irritability or impaired memory.

3. Sex hormone effects: Excess androgen secretion associated with some forms (particularly adrenal carcinomas) can cause hirsutism and menstrual irregularities.

4. HPA dysfunction: In Cushing's Disease, the HPA axis becomes dysfunctional, no longer responsive to negative feedback from cortisol or to stressors that would typically stimulate additional ACTH release.

5. Stress response: Chronic physical and/or psychosocial stress and subsequent hypercortisolism can have widespread negative health effects.

Management Approach

1. Surgical therapy: For Cushing's Disease, treatment involves removal of the pituitary tumor, which can reverse effects in many, but not all, patients.

2. Surgical alternatives: Some patients may require bilateral adrenalectomy when pituitary surgery is insufficient.

3. Nelson syndrome: After bilateral adrenalectomy, be alert for Nelson syndrome (corticotroph tumor progression) with headaches, elevated ACTH, and hyperpigmentation.

4. Adrenal pathology: Adenomas are more common than carcinomas, and carcinomas are more likely to secrete androgens along with cortisol.

5. Rare variants: Bilateral macro- and micro-nodular adrenal hyperplasias, though rare, can cause ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Advanced Management Considerations

1. Medical therapy: Steroidogenesis inhibitors (ketoconazole, metyrapone) may be used when surgery is contraindicated or as bridge therapy.

2. Receptor antagonists: Mifepristone blocks glucocorticoid receptor action and may rapidly improve glucose metabolism.

3. Targeted therapy: Pasireotide targets somatostatin receptors on corticotroph tumors and is particularly useful in persistent/recurrent Cushing's Disease.

4. Radiation options: Various radiation modalities may provide long-term control for pituitary tumors when surgical resection is incomplete.

5. Complex cases: Multiple modality treatment may be necessary for refractory cases, requiring multidisciplinary management.

Long-term Care and Complications

1. Adrenal insufficiency: Post-treatment glucocorticoid replacement protocols and stress dosing education are critical after cure.

2. Cardiovascular risk management: Long-term monitoring and treatment of persistent metabolic syndrome components even after biochemical cure.

3. Quality of life: Recognition and management of persistent cognitive, psychological, and physical symptoms that may persist despite normalization of cortisol.

4. Recurrence monitoring: Regular biochemical monitoring is needed as recurrence is common, especially with certain subtypes.

5. Special populations: Additional considerations for pregnancy, elderly patients, and those with significant comorbidities.