ABIM - Bacterial Endocarditis

Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Here are key facts for American Board of Internal Medicine Certification from the Bacterial Endocarditis tutorial, as well as points of interest at the end that are not directly addressed in this tutorial but should help you prepare for the boards.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for ABIM preparation.

Below is information not explicitly contained within the tutorial but important for ABIM preparation.

- --

VITAL FOR ABIM

Epidemiology & Risk Factors

1. Staphylococcus aureus is the leading cause of infective endocarditis; associated with a high mortality rate due to its aggressive nature and antibiotic resistance.

2. S. aureus exists in the normal human flora, commonly found in the nares (nostrils).

3. Individuals with compromised immune systems and/or prosthetic cardiac devices are at higher risk of developing infective endocarditis.

Pathophysiology

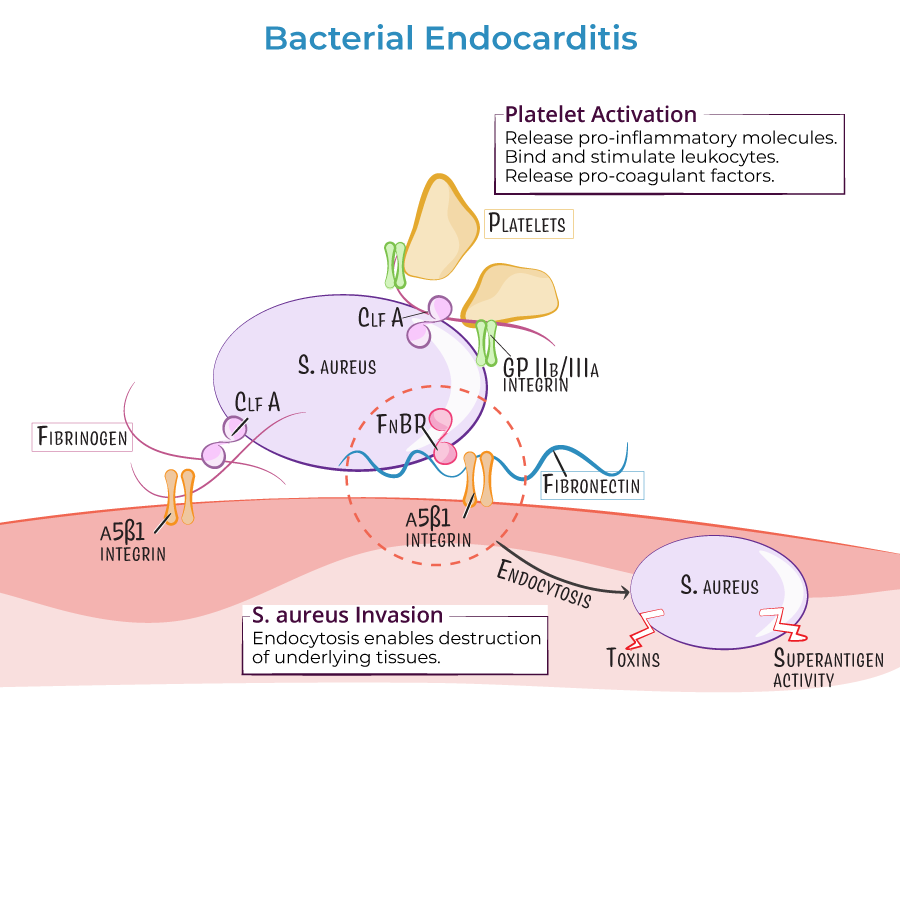

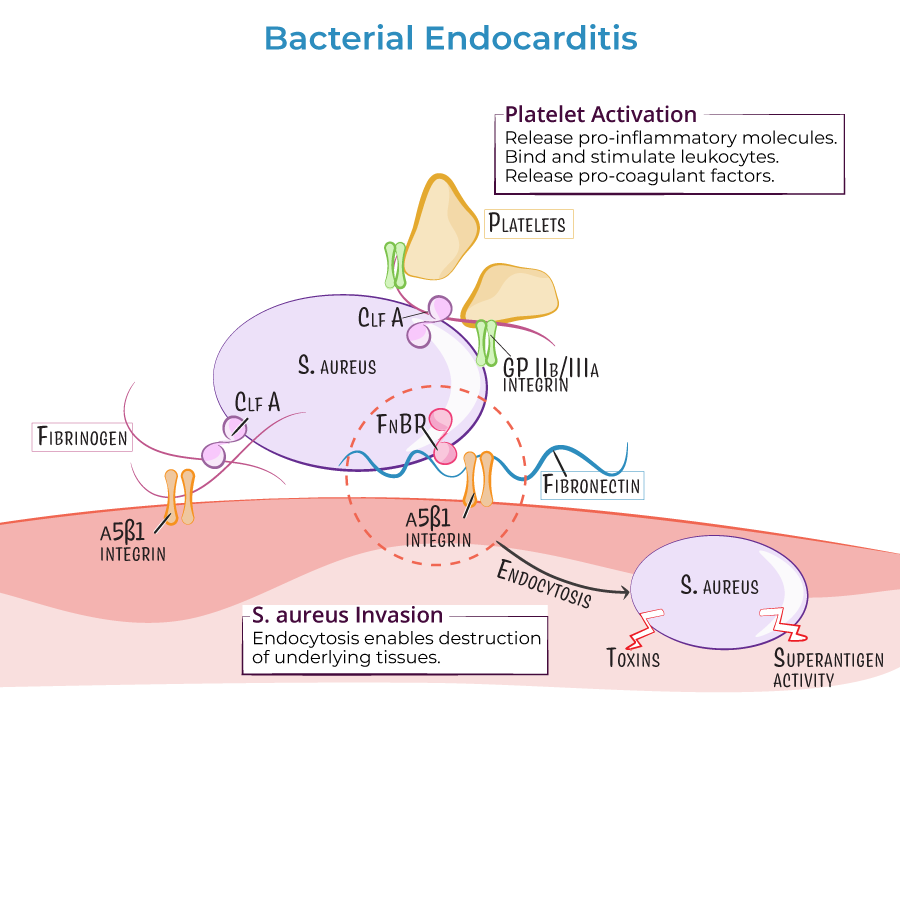

1. S. aureus adheres to endothelial cells and extracellular proteins via surface adhesion protein.

2. S. aureus invades endocardial cells, where it releases toxins and promotes inflammatory processes that are highly destructive to host tissues.

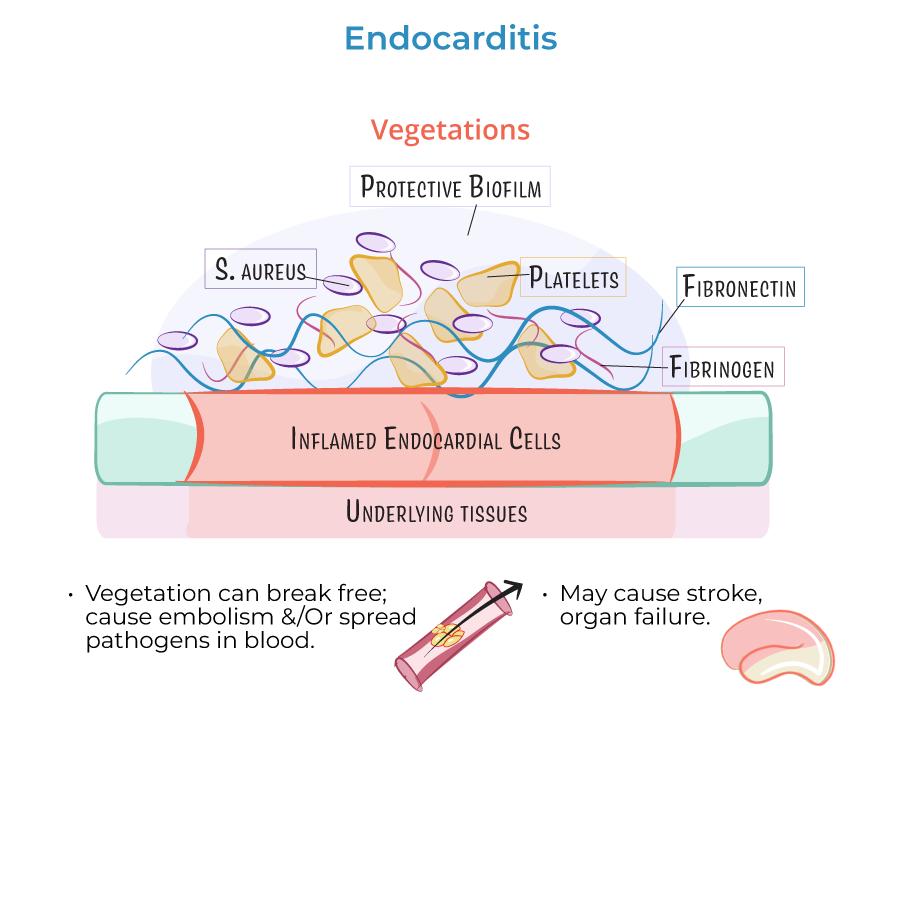

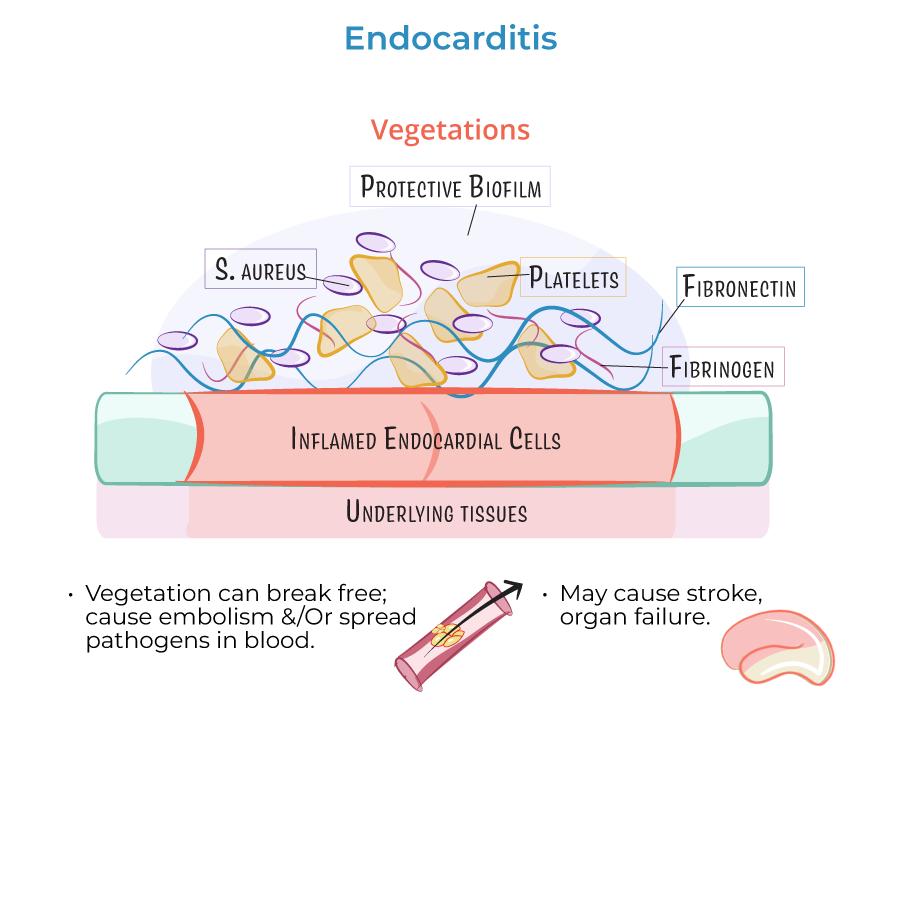

3. Evasion of host defenses occurs via the creation of a protective biofilm and/or phenotype switching to persist as small colony variants.

4. Fibronectin and fibrinogen act as "connecting bridges" that adhere to host cells, platelets, and bacteria to form a thrombotic vegetation.

Treatment Approach

1. Treatment requires prolonged intravenous administration of antibiotics; S. aureus is resistant to penicillin.

2. Methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA) display changes in penicillin-binding proteins to increase tolerance.

3. For MRSA cases, vancomycin or daptomycin, sometimes in combination with other antibiotics, are administered intravenously.

Complications

1. If vegetation breaks free from the valve and travels in the bloodstream, it can easily become lodged in a vessel and cause embolism, even stroke.

2. Endocarditis can affect the atrioventricular valve or walls of the heart (mural endocarditis).

3. S. aureus can "hide" from the host immune system and antibiotic treatments, enabling it to persist and reemerge as a chronic infectious agent.

- --

HIGH YIELD

Virulence Mechanisms

1. The biofilm comprises polysaccharides and proteins that inhibit thrombus destruction, thus allowing S. aureus to proliferate and destroy underlying tissues.

2. Fibronectin adheres to endothelial cells via alpha-5 beta-1 integrins and to S. aureus via surface adhesion proteins such as FnBP.

3. Fibrinogen forms a bridge by adhering to S. aureus via Clumping factor A, and to endocardial cells via alpha-5 beta-1 integrin.

4. Platelets adhere to fibrinogen via integrin GPIIb/IIIa, forming connections that create a thrombus.

Host-Pathogen Interactions

1. Platelet activation induces release of pro-inflammatory molecules, binding and stimulation of leukocytes, and release of pro-coagulation molecules.

2. The S. aureus-fibronectin connection enables endocytosis into the endocardial cell.

3. Within host cells, S. aureus releases toxins and acts as a superantigen to provoke immune responses that ultimately destroy the cells.

4. S. aureus employs phenotypic switching to become small colony variants, allowing it to lie dormant within host tissues.

Antimicrobial Resistance

1. S. aureus is resistant to penicillin, requiring alternative antimicrobial strategies.

2. Methicillin (meticillin), a synthetic derivative of penicillin, has been used to treat S. aureus infections since the 1960s.

3. MRSA strains are increasingly common in both hospital and community settings.

4. The protective biofilm and intracellular location can significantly reduce antibiotic effectiveness.

Clinical Course

1. Infective endocarditis presents with inflammation affecting valves with vegetation blocking blood flow.

2. The aggressive nature of S. aureus enables rapid destruction of valvular tissue.

3. When conditions are favorable, bacteria can reemerge from small colony variants as an infective pathogen.

4. Treatment must address both active infection and the risk of embolic complications.

- --

Beyond the Tutorial

Diagnostic Approach

1. Modified Duke criteria remain the standard for diagnosis, with emphasis on positive blood cultures and echocardiographic findings.

2. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has superior sensitivity to transthoracic (TTE) for detecting vegetations, particularly with prosthetic valves.

3. S. aureus bacteremia should prompt echocardiographic evaluation even in the absence of cardiac symptoms or murmurs due to high risk of endocardial involvement.

Treatment Considerations

1. Initial empiric therapy should cover MRSA in most clinical settings until susceptibilities are available.

2. Duration of therapy typically 4-6 weeks, with timing based on clearance of bacteremia and presence of metastatic foci.

3. Addition of rifampin and gentamicin for prosthetic valve endocarditis is based on synergistic activity against biofilm organisms.

Surgical Management

1. Early surgical intervention may improve outcomes in patients with heart failure, uncontrolled infection, or high risk of embolism.

2. The presence of paravalvular extension, valvular perforation, or abscess formation are strong indications for surgical management.

3. Timing of surgery should balance the risks of embolic complications against the risks of cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with sepsis.