Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Stomach Anatomy

The Stomach

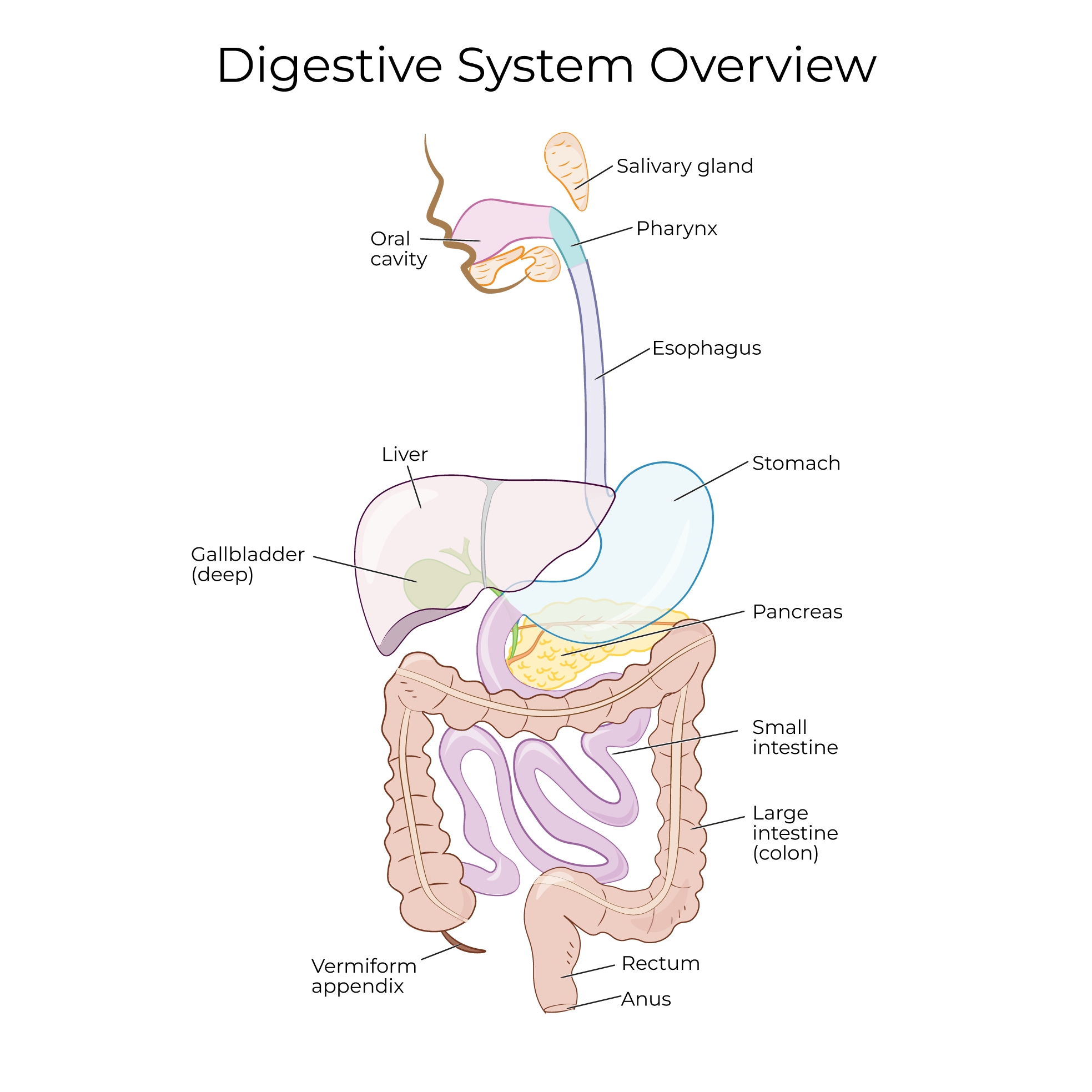

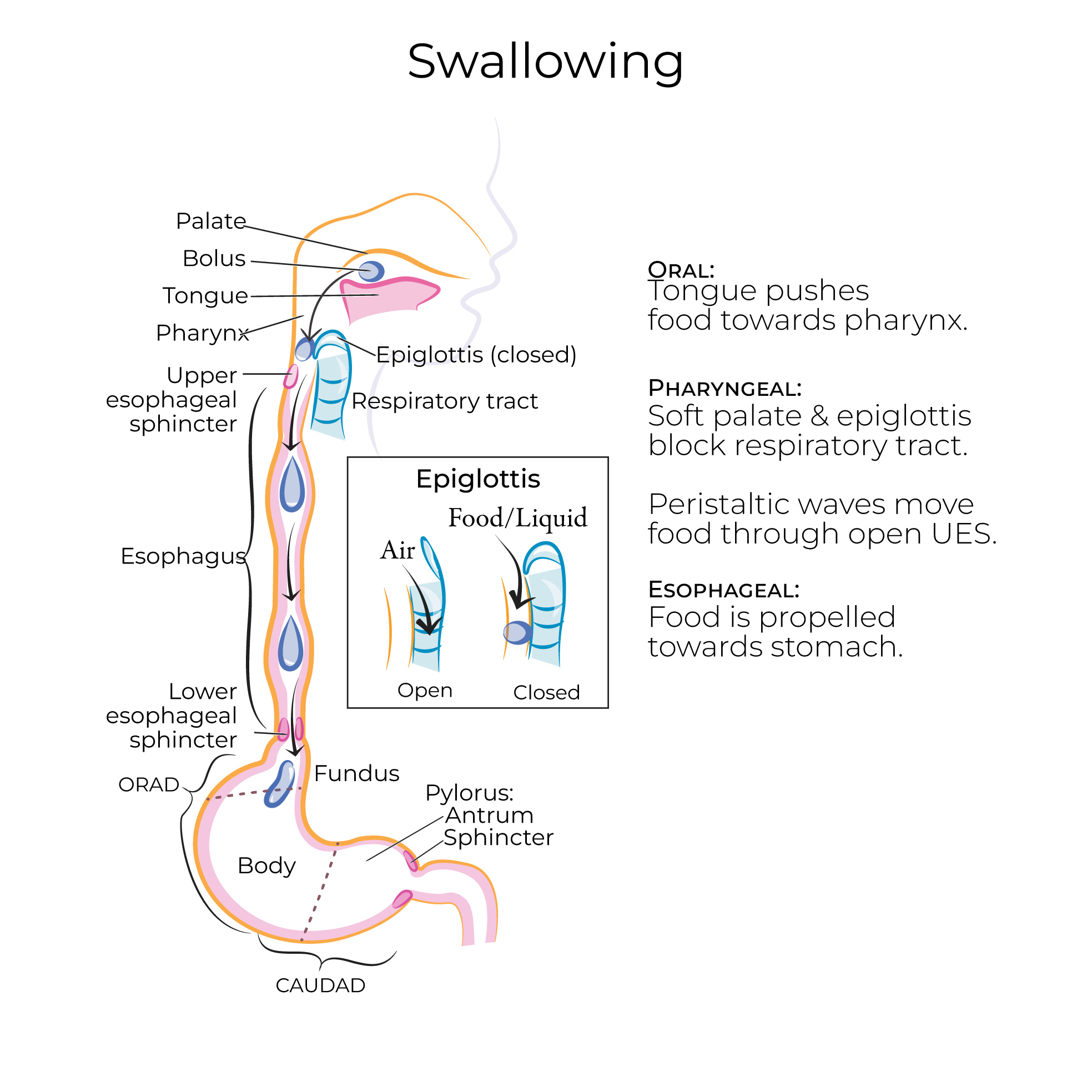

The proximal end of the stomach is continuous with the esophagus, which is a muscular tube that carries foods and liquids from the pharynx to the stomach.

The stomach is a J-shaped organ: its highest point is on the left, and its distal end points to the right and is continuous with the duodenum of the small intestine.

The medial border of the stomach is the lesser curvature, and the lateral border of the stomach is the greater curvature.

The proximal end of the stomach is continuous with the esophagus, which is a muscular tube that carries foods and liquids from the pharynx to the stomach.

The stomach is a J-shaped organ: its highest point is on the left, and its distal end points to the right and is continuous with the duodenum of the small intestine.

The medial border of the stomach is the lesser curvature, and the lateral border of the stomach is the greater curvature.

4 regions of the stomach

The cardiac region is the area surrounding the proximal opening of the stomach (think of this region being near the heart, for cardia).

The cardiac orifice is the opening between the esophagus and the cardiac region; the cardiac sphincter is the thickened area of muscle tissue that regulates the passage of foods and liquids through the cardiac orifice.

The cardiac sphincter is also referred to as the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) or the gastroesophageal sphincter. It is not considered a "true" anatomical sphincter, but, rather, a physiological sphincter, because it is not a well-defined muscular ring.

The cardiac sphincter is tonically contracted to protect the esophagus from the acidic stomach contents. As foods or liquids move through the esophagus, the sphincter relaxes to allow passage to the stomach.

Incomplete closure of the cardiac sphincter can allow the stomach contents to move "backwards" into the esophagus, a condition known as acid reflux. This is commonly referred to as "heartburn" due to the searing sensation felt in the chest.

The fundus is the dome-shaped portion in the upper left region of the stomach.

The body is the middle, and largest portion, of the stomach.

The pyloric region is the distal section of the stomach; we can further subdivide it into the antrum, which is the wider portion, and the canal, which is narrower and is continuous with the duodenum.

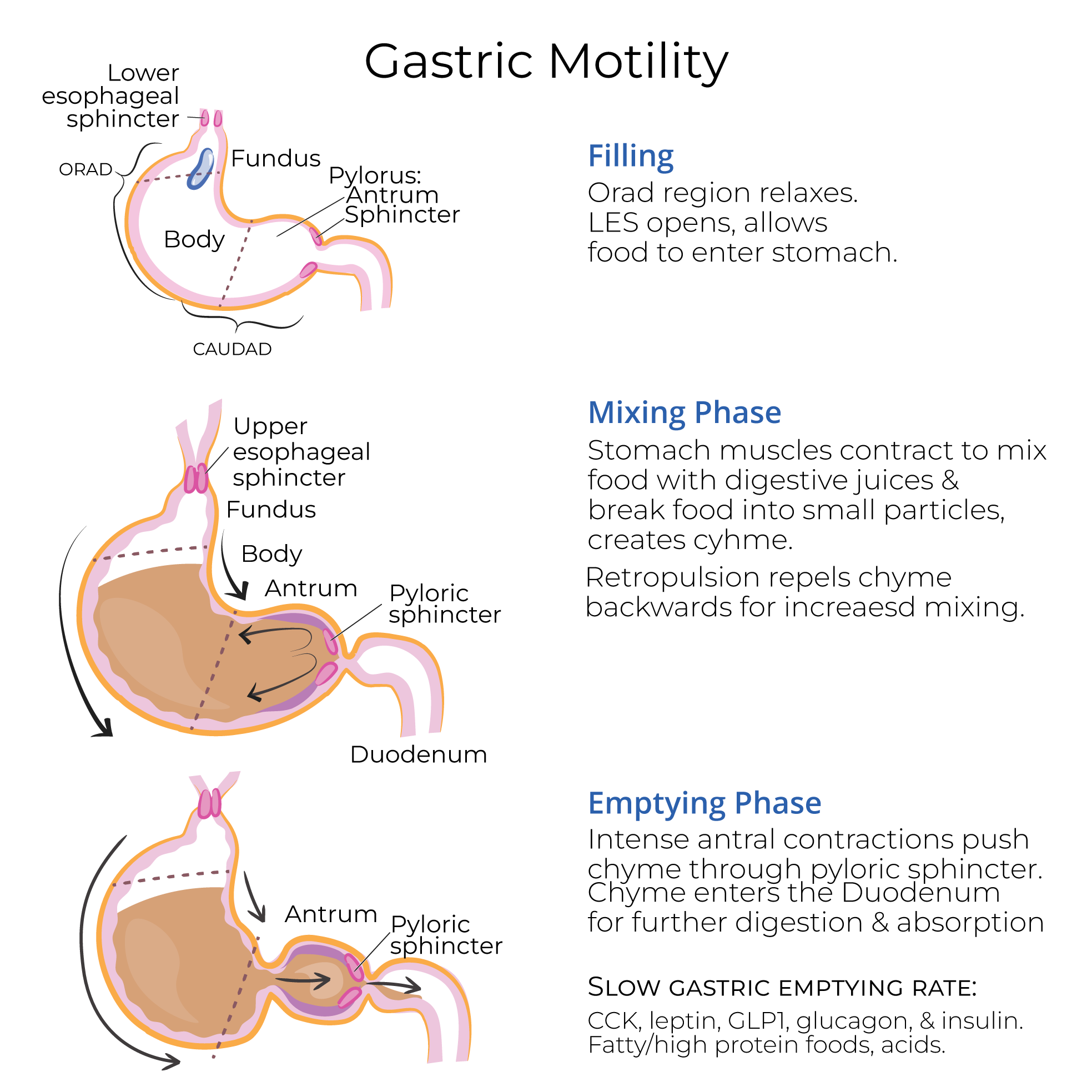

The pyloric sphincter is a ring of muscle that encircles the pyloric orifice, which is the opening between the distal stomach and the duodenum. Intense contractions in the pyloric antral region force small amounts of chyme through the orifice and into the duodenum for further digestion and absorption.

Incomplete closure of the cardiac sphincter can allow the stomach contents to move "backwards" into the esophagus, a condition known as acid reflux. This is commonly referred to as "heartburn" due to the searing sensation felt in the chest.

The fundus is the dome-shaped portion in the upper left region of the stomach.

The body is the middle, and largest portion, of the stomach.

The pyloric region is the distal section of the stomach; we can further subdivide it into the antrum, which is the wider portion, and the canal, which is narrower and is continuous with the duodenum.

The pyloric sphincter is a ring of muscle that encircles the pyloric orifice, which is the opening between the distal stomach and the duodenum. Intense contractions in the pyloric antral region force small amounts of chyme through the orifice and into the duodenum for further digestion and absorption.

The tunics (aka walls) of the stomach

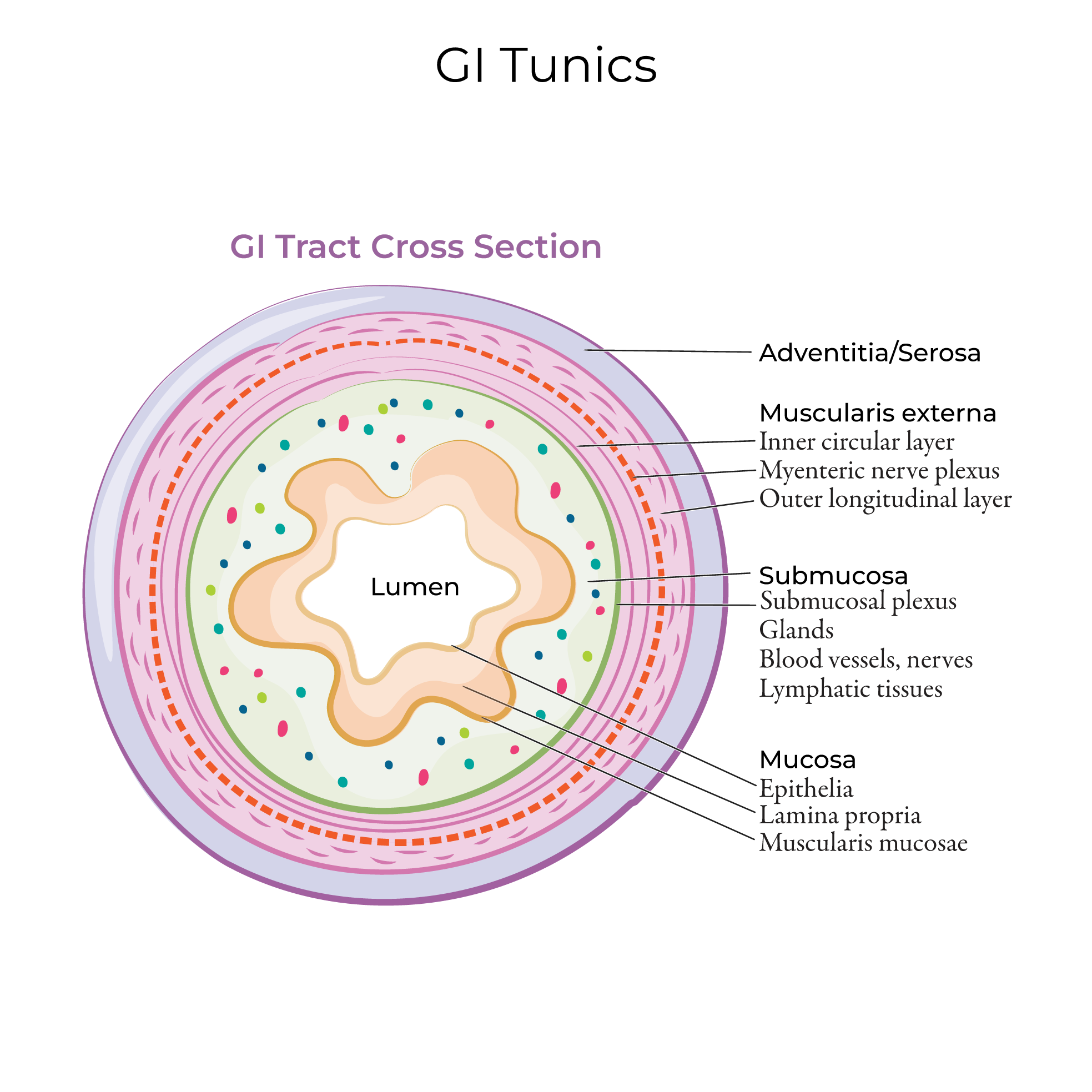

The outermost layer is the serosa, which this is a thin layer of protective connective tissue and mesothelium.

The next layer is the muscularis externa, which comprises three sub-layers of muscle fibers that run in different directions.

First, show the longitudinal layer; its fibers run the length of the stomach.

Then, show the circular layer; its fibers run around the diameter of the stomach.

Lastly, show the deepest layer, the oblique layer; its fibers run diagonally around the stomach.

Recall that other segments of the GI tract have longitudinal and circular layers of muscle. The oblique layer is unique to the stomach, where it facilitates twisting and churning to aid in the mechanical breakdown of food.

Although we've drawn each layer as continuous and of equal thickness, be aware that these layers are thicker in some areas of the stomach and nearly absent in others. This irregular arrangement promotes churning motility in the stomach.

Deep to the muscularis externa is the submucosa; we omit it from our drawing.

Indicate that the innermost layer of the stomach is the mucosa; it lines the stomach.

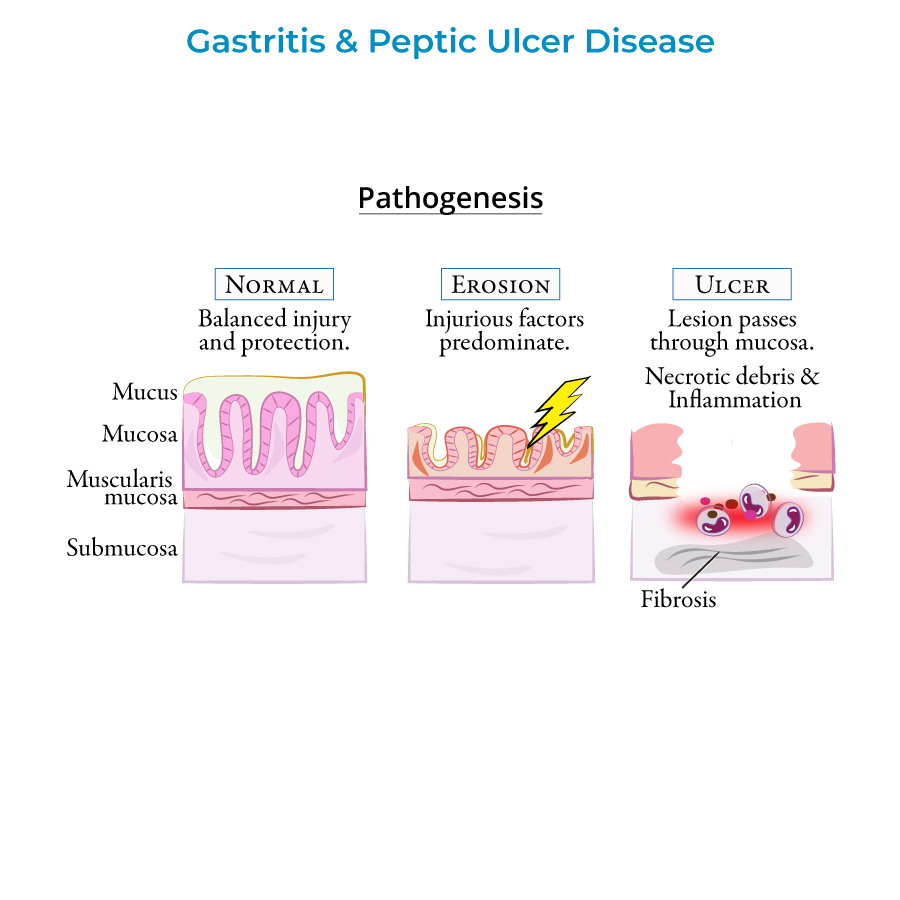

In an empty stomach, the mucosa and submucosal layers wrinkle to form gastric folds, aka gastric rugae; these folds expand to accommodate ingested foods and liquids.

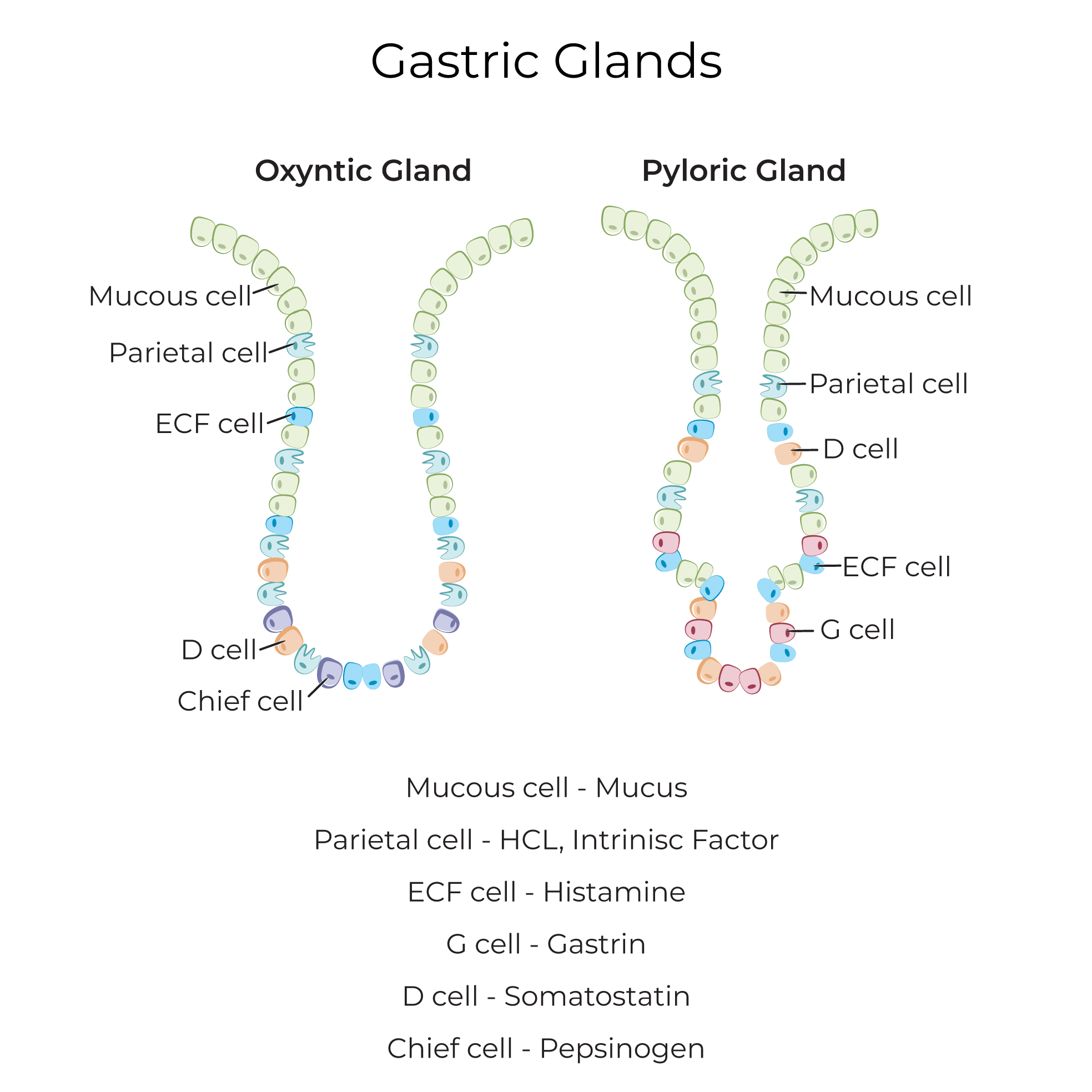

Let's show the gastric mucosa in a little more detail.

Epithelial cells covering the gastric folds.

Then, deeper in the mucosa, show a gastric gland and indicate that it secretes mucus and gastric juices into the gastric pit, which opens to the stomach's lumen.

The outermost layer is the serosa, which this is a thin layer of protective connective tissue and mesothelium.

The next layer is the muscularis externa, which comprises three sub-layers of muscle fibers that run in different directions.

First, show the longitudinal layer; its fibers run the length of the stomach.

Then, show the circular layer; its fibers run around the diameter of the stomach.

Lastly, show the deepest layer, the oblique layer; its fibers run diagonally around the stomach.

Recall that other segments of the GI tract have longitudinal and circular layers of muscle. The oblique layer is unique to the stomach, where it facilitates twisting and churning to aid in the mechanical breakdown of food.

Although we've drawn each layer as continuous and of equal thickness, be aware that these layers are thicker in some areas of the stomach and nearly absent in others. This irregular arrangement promotes churning motility in the stomach.

Deep to the muscularis externa is the submucosa; we omit it from our drawing.

Indicate that the innermost layer of the stomach is the mucosa; it lines the stomach.

In an empty stomach, the mucosa and submucosal layers wrinkle to form gastric folds, aka gastric rugae; these folds expand to accommodate ingested foods and liquids.

Let's show the gastric mucosa in a little more detail.

Epithelial cells covering the gastric folds.

Then, deeper in the mucosa, show a gastric gland and indicate that it secretes mucus and gastric juices into the gastric pit, which opens to the stomach's lumen.

The gastric juices comprise acids and other secretions that chemically break down stomach contents; the gastric mucus protects the lining from these harsh secretions.

The gastric juices comprise acids and other secretions that chemically break down stomach contents; the gastric mucus protects the lining from these harsh secretions.

Clinical Correlations

Gastroenteritis is inflammation of the stomach and intestines caused by infection, often bacterial or viral; common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping.

Most cases of gastroenteritis are self-limiting and require supportive care to prevent dehydration; others require medications to rid the body of the infecting agent.

Gastroenteritis is inflammation of the stomach and intestines caused by infection, often bacterial or viral; common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping.

Most cases of gastroenteritis are self-limiting and require supportive care to prevent dehydration; others require medications to rid the body of the infecting agent.