Start your One-Week Free Trial

Already subscribed? Log in »

Shoulder Joints

Glenohumeral joint

Anterior View

in anterior view, we draw the lateral scapula in articulation with the humerus, and show the clavicle.

Then, we outline the joint capsule, which is lined by a synovial membrane.

The joint capsule is loose and spans from the anatomical neck of the humerus to the neck of the scapula. The looseness of the capsule is especially apparent inferiorly, which accommodates arm abduction. As we'll soon see, tendons of the rotator cuff blend into the external surface of the fibrous capsule.

The anterior capsule is thickened by the superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments.

The glenohumeral ligaments limit the range of movement of the arm; they are taut during external rotation of humerus and relaxed during internal rotation. Together, they resist anterior translation of the humeral head.

Additionally, the middle and inferior ligaments are taut during abduction, whereas the superior is relaxed.

The superior glenohumeral ligament prevents inferior translation of humeral head, especially during shoulder adduction.

The middle glenohumeral ligament lies deep to and blends with the tendon of the subscapularis muscle. It stabilizes the anterior capsule and limits external rotation, especially when arm is in the mid-range of abduction.

The inferior glenohumeral ligament is sling-like; it splits into anterior and posterior bands on either side of the axillary pouch. The inferior stabilizes the humeral head when the arm is abducted above 90 degrees; the anterior band limits external rotation of the arm, whereas the posterior band limits internal rotation.

The transverse humeral ligament extends horizontally between the greater and lesser humeral tubercles; it covers the intertubercular sulcus and holds the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii in place.

The coracohumeral ligament extends between the coracoid process of scapula to the tubercles of the humerus; it limits inferior translation and excessive humeral external rotation.

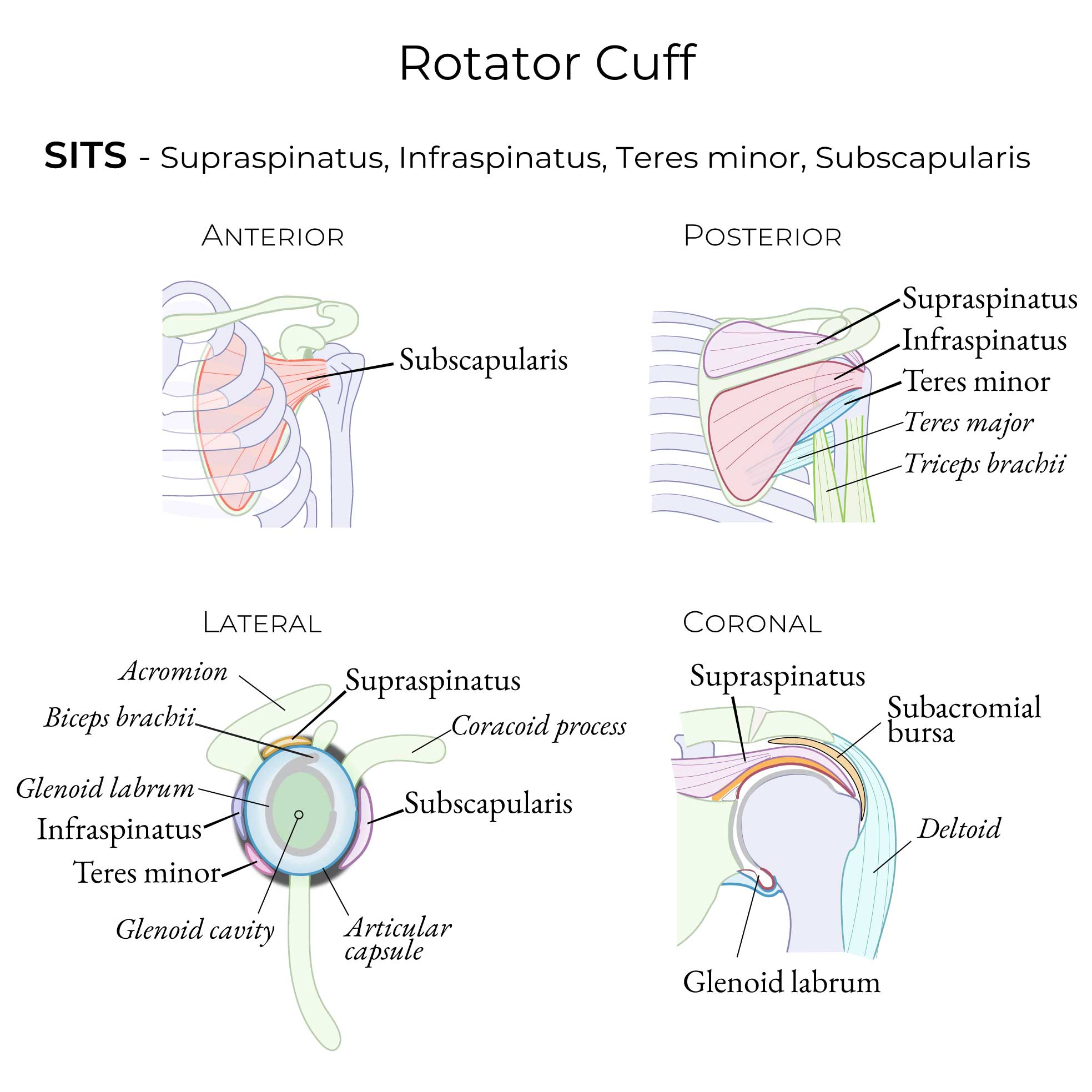

Lateral view - Rotator Cuff & Capsule

We draw the scapula and the glenoid cavity, which is covered in articular cartilage.

The glenoid labrum is the fibrocartilaginous ring along the edge of the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

It is continuous with the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii.

The fibrous joint capsule, has thickened areas that comprise the superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments.

The rotator cuff muscles contribute to the external layers of the capsule as follows:

Anteriorly, subscapularis; superiorly, supraspinatus; posteriorly, infraspinatus and teres minor.

The synovial membrane it attaches to the glenoid labrum; it continues over the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii, which reduces friction between the tendon and bone.

The synovial membrane protrudes though openings in the fibrous capsule to form bursae that reduce friction between the tendons and bones.

The synovial membrane creates a pocket between the subscapularis tendon and the fibrous capsule (specifically the middle glenohumeral ligament); this is the subscapular bursa. This bursa is clinically important because, since it communicates with the joint cavity, opening the subscapularis bursa means entering the joint cavity.

The subacromial bursa is superior; it is sometimes called the deltoid bursa, or the two are combined and referred to as the subacromial/subdeltoid bursae.

There is a bursa between the joint capsule and the coracoid process.

Bursae can become inflamed due to joint overuse or injury, which can cause pain and limit the range of joint movement. Septic bursitis is the result of infection, and requires antibiotic treatment.

Two important weak spots in the glenohumeral joint capsule:

The inferior capsule lacks tendinous or muscular support and is the weakest area of the capsule.

The area between the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons is also relatively weak.

Innervation: subscapular nerve (C5-C6) serves the joint; the suprascapular nerve, axillary nerve, and lateral pectoral nerve serve the joint capsule.

Blood supply: Anterior and posterior circumflex humeral, circumflex scapular and suprascapular arteries.

The synovial membrane it attaches to the glenoid labrum; it continues over the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii, which reduces friction between the tendon and bone.

The synovial membrane protrudes though openings in the fibrous capsule to form bursae that reduce friction between the tendons and bones.

The synovial membrane creates a pocket between the subscapularis tendon and the fibrous capsule (specifically the middle glenohumeral ligament); this is the subscapular bursa. This bursa is clinically important because, since it communicates with the joint cavity, opening the subscapularis bursa means entering the joint cavity.

The subacromial bursa is superior; it is sometimes called the deltoid bursa, or the two are combined and referred to as the subacromial/subdeltoid bursae.

There is a bursa between the joint capsule and the coracoid process.

Bursae can become inflamed due to joint overuse or injury, which can cause pain and limit the range of joint movement. Septic bursitis is the result of infection, and requires antibiotic treatment.

Two important weak spots in the glenohumeral joint capsule:

The inferior capsule lacks tendinous or muscular support and is the weakest area of the capsule.

The area between the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons is also relatively weak.

Innervation: subscapular nerve (C5-C6) serves the joint; the suprascapular nerve, axillary nerve, and lateral pectoral nerve serve the joint capsule.

Blood supply: Anterior and posterior circumflex humeral, circumflex scapular and suprascapular arteries.

Sternoclavicular joints

Acromioclavicular joint

Sternoclavicular joint